Inter-Parliamentary Union

|  |

Name: Inter-Parliamentary Union | |

| Acronym:IPU | |

| Year of foundation: 1889 | |

| Headquarters: Geneva, Switzerland | |

| IPU documents: go to page | |

| Official web site: go to page |

Description

The Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) is the world organization of Parliaments. It is the "focal point for worldwide parliamentary dialogue" and works "for peace and co-operation among peoples and for the firm establishment of representative institutions".

Member States

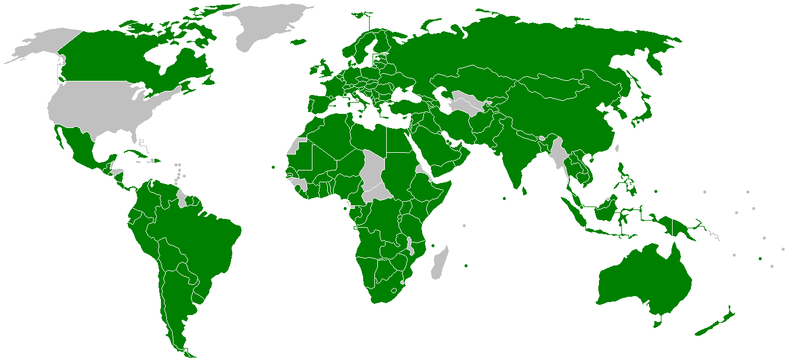

IPU is currently composed of 151 Members:

- Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Andorra, Angola, Argentina, Armenia, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan

- Bahrain, Bangladesh, Belarus, Belgium, Benin, Bolivia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Botswana, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Burundi

- Cambodia, Cameroon, Canada, Cape Verde, Chile, China, Colombia, Comoros, Congo, Costa Rica, Côte d'Ivoire, Croatia, Cuba, Cyprus, Czech Republic

- Democratic Republic of the Congo, Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Denmark, Dominican Republic

- Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Estonia, Ethiopia

- Finland, France

- Gabon, Gambia, Georgia, Germany, Ghana, Greece, Guatemala

- Hungary

- Iceland, India, Indonesia, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Iraq, Ireland, Israel, Italy

- Japan, Jordan

- Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan

- Lao People's Democratic Republic, Latvia, Lebanon, Lesotho, Liberia, Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg

- Malaysia, Maldives, Mali, Malta, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mexico, Monaco, Mongolia, Montenegro, Morocco, Mozambique

- Namibia, Nepal, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Norway

- Oman

- Pakistan, Palau, Palestine, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal

- Qatar

- Republic of Korea, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Russian Federation, Rwanda

- Samoa, San Marino, Sao Tome and Principe, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Serbia, Sierra Leone, Singapore, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Suriname, Sweden, Switzerland, Syrian Arab Republic

- Tajikistan, Thailand, Timor-Leste, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Togo, Tunisia, Turkey

- Uganda, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, United Republic of Tanzania, Uruguay

- Venezuela, Viet Nam

- Yemen

- Zambia, Zimbabwe

The Parliamentary Assemblies of 8 International Organizations are IPU Associate Members:

- Andean Parliament

- Central American Parliament

- East African Legislative Assembly

- European Parliament

- Inter-Parliamentary Committee of the West African Economic and Monetary Union

- Latin American Parliament

- Parliament of the Economic Community of West African States

- Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe

History

The purpose of founding an Inter-Parliamentary Organization in the 19th Century

Founded in 1889 as the first international political organization ever, it since has developed from an organization of individual parliamentarians of mostly European States towards a global organization of 153 Parliaments and eight Associate Members (international parliamentary assemblies) in 2009.

The foundation of the IPU as an organization of individual parliamentarians in 1889 can be traced back to the peace movement of the 19th century, which had elevated international arbitration and disarmament as its main goals. In the year 1888, two parliamentarians, the Englishman William Randal Cremer and the Frenchman Frédéric Passy, took the initiative to convene a conference of parliamentarians in order to call for an arbitration agreement between Great Britain, France, and the US. Shortly before this initiative, a similar Memorial of 234 British parliamentarians, requesting an US-British arbitration agreement and presented to US President Cleveland under the leadership of Cremer, had failed regardless of the support of both US Houses of Parliament. Passy, on the other hand, had successfully pressed for the adoption of a motion in the French Parliament which unfortunately could not be implemented before the end of the session. Thus, the two men, Cremer and Passy, arranged for a first meeting of British and French parliamentarians in October 1888 in Paris which decided to convene a plenary conference of parliamentarians from different countries with the aim to discuss arbitration and disarmament in Paris the year after. On 29 and 30 June 1889, around 100 parliamentarians from nine countries met in Paris in the Hôtel Continental. At the end of the conference, the parliamentarians unanimously passed the following resolution: "Further Interparliamentary Reunions shall take place each year in one of the cities of the various countries represented at the Conference. Thus, the Inter-Parliamentary Union was born.

In the following, the Union very quickly developed an organizational structure whose basic characteristics have not changed to this day. As regards content, until World War I, it dealt with the peaceful settlement of international disputes, especially compulsory arbitration, good offices, mediation and enquiry, with the limitation of armaments, problems of neutrality, the rules of warfare at sea and in the air, individual rights, and private international law. Its main success, however, was the establishment of the Hague Court of Justice at the first Hague Conference in 1899 which was decisively influenced by an IPU draft treaty. The IPU draft had been adopted in 1895 and was contained in a so-called "Memorial to the Powers" which the author of the Memorial, Baron Descamps, had sent to governments. The Union had been pressing for the convocation of an international governmental congress for the peaceful settlement of disputes through arbitration since 1894. However, the initiative to call for such a conference - first reduced to the question of armaments and only later enlarged to include also the question of good offices, mediation and voluntary arbitration - was taken by the Russian tsar Nicholas II, influenced by one of his diplomats who had participated in an IPU Conference some years earlier. The result of this first Hague Conference - the first conference convened in order to prevent future wars and to codify humanitarian law instead of merely concluding a peace treaty - is widely known: It adopted the Hague Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes, which also established the Hague Court of Arbitration, the first international court at all. With regard to that court, the governmental drafts for the convention undoubtedly were influenced by the Union's Memorial. The author of the Memorial, the parliamentarian Lord Descamps, was the rapporteur of the respective committee. In the following, individual IPU members also were influential in bringing about the first arbitration proceedings before the Court in 1902 and were part of the proceedings.

The Union similarly was instrumental in launching the convocation of the second Hague Conference in 1907, when the Secretary-General of the Union, Albert Gobat, delivered a personal message in the name of the Union to US President Roosevelt in 1904. However, the IPU's model draft treaty of 1906, aimed at introducing compulsory arbitration, was less successful than its forerunner of 1895. Even though accepted, after some changes, by the majority of governmental representatives present, it could not be adopted given the necessity of unanimity requested at that time. Altogether, it is no exaggeration to conclude that the Union at the beginning of the last century contributed significantly to the development and codification of international customary law in the field of arbitration. Moreover, with its work on the permanent organization of the Hague Conferences, the IPU played some role in the setting-up of the League of Nations after World War I. Especially, an IPU draft on the establishment of a permanent court was taken as the basis for negotiations on the Statute of the League's Permanent Court of International Justice in 1920. Due to these first developments, it is not surprising that during the first forty years of existence of the Union, eleven Nobel Peace Prize Winners, among them one of the two first in 1901, originated from the ranks of the IPU. The most impressive occurrence, however, from the viewpoint of international democracy, was the discussion within the Union, on the basis of an American proposal, of the establishment of a world parliament with full parliamentary powers from 1904 onwards. At that time already, without an international organization in existence, voices within the Union existed who openly propagated a role for the IPU itself as an embryo of a future world parliament. In the following, the quarrel over the question of timing and the confusion over a clear distinction between governmental and parliamentary tasks and organs at the international level, since at that time neither international organizations nor any other embryonic form of world government existed, lead to the quasi-abandonment of the idea. Another controversy was the question of whether the role of a world parliament should be assigned to the Union itself. In the end, a governmental organization of the world was promoted rather than some representation of the people as such. Yet, the intention of the Union, namely, to reduce governmental power in foreign affairs, remained one of its main goals throughout that time: "[L]a Conférence interparlementaire a été fondée précisément dans le but de réduire le rôle de la diplomatie, et d'augmenter l'influence des parlements sur les affaires internationales à l'effet de régler celles-ci conformément aux lois de la justice."

The success of the Union at that time and its good echo in public opinion can be put down to the fact that the Union impressed through a new form of international administrative and conference organization, the activist commitment of its individual membership rooted in the peace movement of its time, but often at the same time representing its governments at international conferences, the expertise-based elaboration of new and revolutionary ideas, frequently in form of international draft treaties, directed towards a progressive development of international law, and the concentration on mainly one goal, namely, "peace through arbitration", with the aim of establishing a world-wide order of law and peace. Its clumsy inner organization, its dependence on elections and the existence of Parliaments, the emphasizing of inner reform instead of external assertion, the absence of social-democrats within the organization, its slow drifting away from the peace movement on the one hand, and the public and the people on the other, but also its hesitation to address current problems on the political agenda and its holding to the principle of non-interference in internal affairs, all this, however, became a stumbling-block for the Union's future success.

Hoping for parliamentary surmounting of the international democratic deficit between the Wars

The reputation of the Union based on its organizational and content-related successes continued after World War I, even though it had failed on a popular informative as well as a democratic political-power-related level before the war. One of the drafts for the Covenant of the League of Nations, the so-called plan of Lord Robert Cecil, British delegate to the Paris Peace Conference, of 14 January 1919, provided for the possibility of setting up "a periodical congress of delegates of the Parliaments of the States belonging to the League, as a development out of the existing Inter-Parliamentary Union. … The congress would thus cover the ground that is at present occupied by the periodical Hague Conference and also[, perhaps,] the ground claimed by the Socialist International". The IPU reference in this still informal draft was not carried over into the subsequent official proposals of the British government. However, for many inter-parliamentarians it remained a source of reference with regard to the perspective of an official role of the IPU. Moreover, even though the Union had not been able to prevent World War I, war also could not prevent inter-parliamentarianism from flourishing between the Wars. Nevertheless, power had to be given up to the first international governmental organization established to prevent war, the League of Nations.

Between the two World Wars, the IPU intensified its work in the field of peaceful settlement of international disputes, the reduction of armaments and international security, and the development of the rules of warfare, but also dealt with support for the League of Nations, the further codification and development of international law, the promotion and improvement of the representative system, the protection of national minorities, colonial problems, economic questions, social and humanitarian policy, and intellectual relations. Its work was less sensational, but more profound than before the War - a result of the work of renowned and progressive scholars, such as La Fontaine, Schücking, or V. V. Pella, who, as parliamentarians, put much effort into inter-parliamentary affairs. Thus, the Union dared to venture into new and unregulated fields of law, such as into international criminal law, the rights of minorities, or consequent disarmament. Finally, it was also successful in helping treaties to be ratified at the national level.

With regard to its own role, however, the Union did not realize that the balance of power in foreign affairs had changed in favor of governmental representatives at the international arena. Its old enemy, namely, monarchy, had disappeared and a new one had not yet been born. Main goal of the Union now was the support of the League of Nations - a League, which, in the IPU's view, would have to become universal -, but the conception of the Union's own role in international democratization was shaped by a jealous fear of loosing freedom of action and independence. Thus, those calling for a more than complementing, merely semi-official role of the Union in the framework of the League did not gain a hearing. The Union, by not pursuing these ideas further, lost terrain without a fight. Nevertheless, the relations with the League, which even employed liaison officers for IPU affairs, were good – the Union after all was not an enemy to the League. It had meanwhile moved to Geneva and still many of its members at the same time were governmental representatives at meetings of the League. But the League dealt with the same questions as the Union and even tackled so-called apolitical issues, such as health issues, scientific and cultural cooperation, refugee questions and migration, or trade in women and children, and this in a much broader and a very successful manner. Moreover, the IPU also remained silent with regard to all the crises straining the international system in the 1930s, even though those concerned the Union's main goals and purposes, namely, the peaceful settlement of disputes, disarmament, the rules of warfare and the development of the League.

In the end, the Union was relegated to the backbench of an international system whose coming into being it had itself fervently promoted and supported. The only advantages which could make it stand out from the League were its universal approach and its work for dialogue and cooperation among peoples, between victors and vanquished, between supporters and opponents of the League, and between adepts of the status quo and revisionists.

After World War II: Recognizing facts and struggling for renewed international relevance

After World War II, the Union was mostly forgotten in political circles. Inter-parliamentarians did not contribute in any way to post-war reconstruction. The prestige of the Union had faded, it was running out of money and the high-level contacts to international organizations and governmental circles which were so prominent before the War were slowly crumbling, given the increasing lack of representatives working in parliamentary as well as governmental circles at the same time. The Union itself did not seem to be willing to come closer to the new international organization replacing the League, the United Nations. The IPU stayed in Geneva and did not move to New York. It changed its Statutes and Rules only 25 years later, namely, in 1971, to expressly mention support to the objectives of the UN - instead of support to a universal organization of nations in general. Moreover, it did not search for a suitable status of the Union at the UN. Given the fact that the Union's parliamentarians themselves could not reach agreement on an attempt to acquire treaty recognition by governments, the Union only was given consultative status with ECOSOC, with only little possibilities to influence politics and relegating the parliamentary organization to the status of an NGO.

Institutions and decision-making process

The organization developed a structure largely comparable to its present structure already throughout the first five years of its existence. In 1894, the first Statutes of the Inter-Parliamentary Conference were adopted. The governance structure provided for a four-fold (parliamentary) structure: the General Assembly, the political organ of the Union, the Assembly of Delegates with two members of each parliamentary group, preparing the General Assembly of the Conference, a Bureau, with one representative of each group, as the management and executive organ at the same time, and a President presiding over the Bureau. Today, these tasks are taken over by the Assembly (political organ), the Governing Council (governing organ), the Executive Committee and the Secretariat (separated tasks, management organ and executive organ), and the IPU President (political head of the organization and ex officio President of the Governing Council). The organization is thus single-headed (President), multi-headed (Executive Committee) and self-regulatory (Governing Council) in once.

The Secretariat and the Secretary-General

The Secretariat of the Union comprises the totality of the staff of the organisation under the direction of the Secretary-General of the Union. It is independent from Member parliaments – apart from the election of the Secretary-General – and with theoretically mere organizational powers, even though in practice the Secretary-General's influence extends into the political.

The Assembly

The Assembly shall be composed of parliamentarians designated as delegates by the Members of the Union. The Assembly is assisted in its work by Standing Committees, whose number and terms of reference are determined by the Governing Council; Standing Committees shall normally prepare reports and draft resolutions for the Assembly. No one delegate may record more than ten votes. It meets twice a year.

The Governing Council

The Governing Council shall normally hold two sessions a year. The Governing Council shall be composed of three representatives from each Member of the Union. The term of office of a member of the Governing Council shall last from one Assembly to the next and all the members of the Governing Council must be sitting members of Parliament. The Governing Council shall elect the President of the Inter-Parliamentary Union for a period of three years. It elects the members of the Executive Committee and appoints the Secretary General of the Union.

The Executive Committee

In accordance with the Union's Statutes, this 17-member body oversees the administration of the Inter-Parliamentary Union and provides advice to the Governing Council.

The 15 members of the Executive Committee are elected by the Council for a four-year term. The President of the IPU is an ex officio member and President of the Committee. The President of the Co-ordinating Committee of Women Parliamentarians is an ex officio member of the Executive Committee for a two-year term which can be renewed once. Not less than 12 members of the Executive Committee are elected from among members of the Governing Council and at least three members must be women.

The Executive Committee advises the Council on matters relating to affiliation and reaffiliation to the Union, fixes the date and place of Council sessions and establishes their provisional agenda. It also proposes to the Council the annual work programme and budget of the Union. The Executive Committee controls the administration of the Secretariat as well its activities in the execution of the decisions taken by the Assembly and the Council.