World Trade Organization

|  |

Name: World Trade Organization | |

| Acronym: WTO | |

Year of foundation: 1947 (GATT);1995 (WTO) | |

Headquarters: Geneva, Switzerland | |

WTO documents: go to page | |

WTO official web site: go to page |

Description

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is an economic institution created with the aim to liberalize international trade.

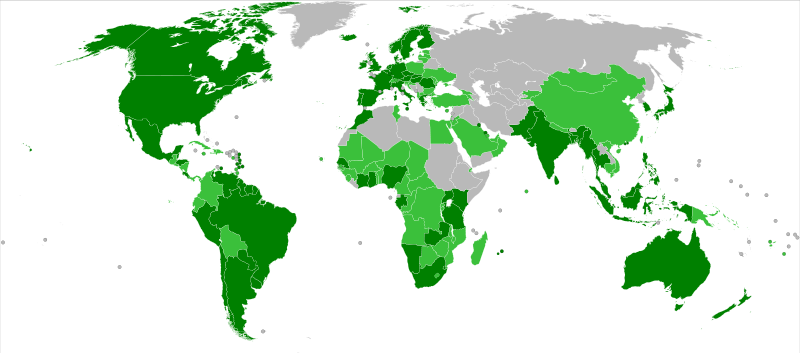

Member states

The WTO has 153 members states, namely:

Albania, Angola, Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Armenia, Australia, Austria, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Barbados, Belgium, Belize, Benin, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Brunei Darussalam, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cambodia, Cameroon, Canada, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Chile, China, Colombia, Congo, Costa Rica, Côte d'Ivoire, Croatia, Cuba, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Denmark, Djibouti, Dominica, El Salvador, Estonia, European Union, Fiji, Finland, France, Gabon, Gambia, Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Georgia, Germany, Ghana, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, Greece, Grenada, Guatemala, Guinea, Haiti, Guinea Bissau, Guyana, Honduras, Hong Kong, Hungary, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Jordan, Kenya, Republic of Korea, Kuwait, Kyrgyz Republic, Latvia, Lesotho, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macao, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Maldives, Mali, Malta, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mexico, Moldova, Mongolia, Mozambique, Namibia, Nepal, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Myanmar, Morocco, Niger, Nigeria, Norway, Oman, Pakistan, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Qatar, Romania, Rwanda, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent & the Grenadines, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Singapore, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Solomon Islands, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Suriname, Sweden, Swaziland, Switzerland, Chinese Taipei, Tanzania, Thailand, Tonga, Trinidad and Tobago, Togo, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, Uruguay, United States of America, Venezuela, Viet Nam, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

History

The WTO forerunners: the ITO and the GATT

Countries have entered into bilateral agreements to liberalize trade between them as early as the seventeenth century. However, it was not until the aftermath of World War II that a multilateral agreement on trade liberalization was concluded. When the establishment of the International Monetary Fund and the Bank for Reconstruction and Development were agreed at Bretton Woods in 1944, there was a perceived need to create another multilateral organization for the liberalization of trade between countries. Initially, the negotiating countries had an ambitious plan to adopt an agreement for the reduction of tariffs and some non-tariff barriers and an agreement for the establishment of an International Trade Organization (ITO) with a far-reaching remit. The charter for the ITO foresaw commitments for countries in foreign investment, labour standards, restrictive business practices, international commodity arrangements and dispute settlement through the referral of disputes to the International Court of Justice. The countries could agree relatively easily on the provisions relating to tariff reductions and other non-tariff barriers in the form of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). But by 1951, the US ceased to support the establishment of an ITO with the more far-reaching remit and strong institutional structure. The GATT, which had been considered an integral part of the effort to establish an ITO, came into being on its own as eight of the 23 signatories to the GATT decided to apply the agreement provisionally between them as of 1 January 1948. Other countries later acceded to the Protocol of Provisional Application and the GATT turned out to be far from temporary as it provided the basis for multilateral trade liberalization until 31 December 1994.

The GATT 1947 contained provisions for the binding of tariffs on a most-favoured nation basis and prohibited quantitative restrictions and discriminatory internal taxes and regulations, amongst others. However, the rules of the GATT were weakened by several factors. The permission of grandfathering considerably reduced the impact of the GATT as it essentially made it applicable to future laws only.Another debilitating factor for the GATT was its weak dispute settlement. In order to be adopted a GATT panel or working party report had to be agreed to by all contracting parties, including the loosing party. Finally, the contracting parties adopted foreign restrictive trade practices that contravened the aims and spirit of the GATT. Despite being institutionally ill-equipped for promoting the liberalization of trade, the GATT was remarkably successful in reducing tariffs among the contracting parties, in settling disputes non-contentiously and in attracting further membership. When, as result of low tariffs, the importance of non-tariff barriers to trade became more apparent, however, further liberalization was more difficult to achieve. Ultimately, the GATT was institutionally too weak to handle these politically more salient barriers amidst a greater diversity of contracting parties.

The creation of the WTO

As tariffs were progressively reduced, it became clear that the GATT’s disciplines on other trade barriers and unfair trade practices were insufficient. In the Kennedy and the Tokyo Round the contracting parties adopted additional disciplines (called Codes) on topics such as anti-dumping, subsidies and technical barriers to trade. But these Codes were inconsistent with the MFN principle and rendered the international legal environment for international trade complex, messy and non-uniform. It also soon became clear that the GATT dispute settlement mechanism was not able to resolve the more politically-laden cases of non-tariff barriers. There was a wide-felt need to tidy up the GATT’s Codes and reform the dispute settlement system.

Initially, the creation of an international organization for the liberalization of trade was not an issue in the Uruguay Round negotiations, which had a heavy focus on dispute settlement reform and new areas of liberalization (agricultural trade, intellectual property and services). While Canada and the EC proposed the establishment of a multilateral trade organization, the US was opposed to it, concerned about preserving consensual decision-making and its domestic sovereignty. The US continued to hold out on agreeing to the establishment of a World Trade Organization until late 1993. With the Uruguay Round successfully concluded, the new agreements and organization became operation in 1995. The negotiating countries created the World Trade Organization as an international organization with legal personality. They also reformed the dispute settlement mechanism, inter alia by creating a standing appellate tribunal (the Appellate Body), by giving the WTO dispute settlement mechanism compulsory jurisdiction over all disputes arising under the covered agreements of the WTO, by removing the possibility for blocking the adoption of reports unless all WTO members agree to it (the so-called reverse consensus rule) and by strengthening the mechanism for overseeing the implementation of WTO dispute settlement reports.They also transformed the many plurilateral agreements into a single undertaking. Finally, they also expanded the substantive coverage of trade liberalization and added considerably detailed rules in areas such as agricultural trade, domestic health and food safety legislation, services liberalization and intellectual property protection.

The Doha Development Round

Although the trade liberalization achieved in the Uruguay Round was substantial overall, significant liberalization in agriculture and services could not be achieved, creating a need for a further negotiations. Because of massive anti-globalization protests, the Seattle meeting failed to produce agreement on a negotiating mandate. It was not until the next meeting in Doha in 2001 that the WTO members could finally agree on a work package and start actual negotiations. The 2003 Cancún conference failed to complete the negotiations due to disaccord between developing and developed countries over agricultural trade liberalization. In the 2004 framework, members have agreed substantial improvement in market access for agricultural products, the setting of a date for the elimination of all export subsidies and substantial reductions in trade-distorting domestic subsidies with an upfront reduction of 20% by developed countries.

At Doha, the mandate for the Negotiation Round was baptized the Doha Development Agenda (DDA) and was meant to focus heavily on concerns of developing countries. It comprises issues such as longer transition periods for developing countries to comply with WTO rules, exemption from or restraint in imposition of measures to combat unfair trade practices when developing countries are concerned and technical assistance. Crucially, the negotiations on implementation aim at identifying which special and differential treatment provisions in favour of developing countries are mandatory and to consider the implications of turning non-mandatory ones into mandatory ones. The developed countries have agreed to giving duty and quota-free access to products of least-developed countries and the Doha Development Agenda Global Trust Fund with a 24 million Swiss francs to finance the WTO’s technical assistance to developing countries has been created. Another important concern for developing countries is the liberalization of agricultural trade. In the 2004 framework, members have agreed substantial improvement in market access for agricultural products, the setting of a date for the elimination of all export subsidies and substantial reductions in trade-distorting domestic subsidies with an upfront reduction of 20% by developed countries. In the area of market access for non-agricultural goods, negotiations are to focus on the reduction of elimination of tariff peaks and tariff escalation on products of export interest to developing countries. As part of the negotiations on TRIPS (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights), the Doha conference produced the Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health, which affirms and clarifies the right of developing countries to use compulsory licensing and parallel importing to respond to public health crisis. The members were also able to agree on allowing non-developing countries to manufacture drugs under a compulsory license if the developing country has insufficient manufacturing capacity to produce generics. Members disagree on whether negotiations on geographical indications are not products other than wines and spirits are called for. Other parts of the DDA focus on improving existing WTO disciplines regarding unfair trade practices, regional trade agreements, the relationship between WTO rules and multilateral environmental agreements and dispute settlement.

WTO structure and decision-making procedures

The function of the WTO is to facilitate the implementation, administration and operation and to further the objectives of the WTO Agreement and its other covered agreements and to provide a forum for negotiation amongst the WTO members on existing agreements and new issues concerning their multilateral trade relations.

Ministerial Conference

The Ministerial Conference is the top decision-making body of the WTO. It meets at least every two years, it can take decisions on any matter arising under the multilateral trade agreements and negotiates on further rules. This includes the power to adopt interpretations and amendments of the WTO Agreements, to grant waivers of obligations and accept the accession of new members.

The General Council

In between meetings of the Ministerial Conference, the General Council carries out the function of the Ministerial Conference. It is composed of representatives of the member states' governements, and acts also as the Trade Policy Review Mechanism and as the Dispute Settlement Body but with two different chairpersons. The General Council directs the Council for Trade in Goods, the Council for Trade in Services and the TRIPS Council and Committees on Trade and Environment, Trade and Development, Balance of Payments Restrictions, Regional Trade Agreements and on Budget, Finance and Administration, as well as the working parties on accession and two further working groups.

The Secretariat

The WTO Secretariat has a largely auxiliary function. It provides technical support for the various WTO governing bodies, technical assistance for developing countries, advice and organizational support for accession negotiations, conducts trade policy analyses, collects statistics and provides legal advice and assistance to dispute settlement panels and the Appellate Body. The Secretariat is headed by the Director-General of the WTO who is appointed by the General Council. As head of the Trade Negotiations Committee, the Director-General oversees the conduct of negotiations in the Doha Ministerial Round. Although having no formal decision-making power, the Director-General and the Secretariat staff assisting panels and the Appellate Body have an important informal influence. The Director-General can steer negotiations, set negotiation deadlines and influence the conduct of negotiations via public statements. Members of the Secretariat are appointed as international officials and the WTO Agreement makes clear that their responsibilities shall be exclusively international in character and that they shall not act under instruction from members or any other authority external to the WTO.

Jurisdiction system

The WTO has a two-tiered system of dispute settlement with jurisdiction of over all matters arising under the WTO agreements. The first level of dispute settlement is the panel, composed of three ad-hoc panellists who are not officials of the Secretariat. Panellists for the case are drawn from a pre-established roster indicating names of well-qualified individuals. The roster includes private lawyers, academics and current or former representatives of governments. Panellists serve in their individual capacity and can be removed in cases of conflict of interest and must be removed if they are nationals of the disputing parties. The parties to a dispute can select the three panellists themselves by mutual agreement. They can also appoint five panellists if they so mutually agree. Failing their agreement, the Director-General appoints the panellists. This happens in more than 50% of the cases.

Panel reports can be appealed to the Appellate Body on issues of law. The Appellate Body has a standing membership of seven. Three members sit on a case but they discuss their views with the other members of the Appellate Body. Members of the Appellate Body are appointed in their individual capacity and should not accept instructions from any international, governmental or private source. The members shall be broadly representative of the membership of the WTO and they should posses recognized authority and a demonstrated expertise in law, internal trade and the subject matter of the WTO Agreements. They serve a four-year term and may be reappointed once.

The Dispute Settlement Body adopts reports unless the members decide by consensus not to adopt the report. The Dispute Settlement Body, panels and the Appellate Body also keep under review the implementation of WTO dispute settlement reports. A loosing defending member has to report to the Dispute Settlement Body about its implementation. If it fails to implement within a reasonable period of time, the Dispute Settlement Body authorizes the winning complaining member(s) to take countermeasures, if it/they so request. If there is disagreement about measures taken to comply with a dispute settlement report, the parties have to refer their dispute to the original panel with again a possibility of appeal to the Appellate Body. The DSU foresees arbitration over the time period for implementation and over the amount of retaliation that can be imposed. The DSU foresees good offices, conciliation, mediation and binding arbitration as alternatives to dispute settlement panels but their actual use has remained very minor.

The Dispute Settlement Mechanism is without doubt the most important element of supranationalism in the WTO. In comparison to international tribunals such as the International Court of Justice, the WTO panels and Appellate Body have had a heavy caseload. Members have consented to the compulsory jurisdiction of the WTO dispute settlement mechanism over disputes arising under the covered agreements of the WTO and dispute settlement reports become adopted automatically unless the WTO membership decides by consensus not to adopt the report (the so-called reverse consensus rule). Although the Dispute Settlement Understanding foresees more diplomatic means of dispute resolution, almost all matters that remained contentious after initial consultations have resulted in the establishment of a panel. Panels and the Appellate Body have thus obtained the possibility to review acts that hitherto fell into the sole domestic jurisdiction of WTO members. Their jurisdiction allows them to declare that domestic acts are inconsistent with WTO Agreements and to make suggestions for implementation but they cannot annul the domestic act. WTO dispute settlement also has a relatively strong enforcement mechanism. A loosing party has to implement the recommendations of the report (this generally requires it to remove the inconsistency with WTO law by either removing the measure altogether or amending it) and has to report on its implementation to the Dispute Settlement Body. If it fails to implement, the winning party can either seek the authorization to take countermeasures against the loosing party (in the form of imposing higher tariffs or erecting other barriers to trade) or seek concessions from it (in the form of increased market access in other sectors), subject to the loosing party’s agreement.

Decision-making within WTO

In the WTO consensual decision-making prevails in practice. Consensus is deemed to exist if no member present at the meeting where the decision is taken formally objects to it. The WTO Agreement provides that a decision can be taken by a majority if consensus cannot be reached. The simple majority rule is the default decision rule, unless other majority requirements are stipulated. A ¾ majority is required for decisions on interpretations and waivers and a 2/3 majority is required for decisions on accession of new members. Any member of the WTO or any Council may submit a proposal to amend provisions of the WTO Agreements. If consensus on the acceptance of the proposed amendment cannot be reached, 2/3 of the members can decide to submit the proposal for amendment for acceptance to the members. Special rules of acceptance apply for the entry into force of amendments, depending on whether basic principles (MFN, WTO decision-making), rights-altering and non-rights-altering amendments are concerned.

In practice, the WTO takes all decisions by consensus and retains a strong intergovernmental element. However, it would be mistaken to consider that its rules are actually consented to by every state member to the WTO for several reasons: First, draft rules are generally negotiated among the key players (Canada, EU, Japan, USA and several big developing countries), leaving individual, small countries dependent on multilateral rules for market access with little option but to accept them.Second, most rules of the WTO have to be accepted as a package (the so-called single undertaking). Countries that accept the package may still find individual agreements objectionable. These factors confer a de facto supranational element on WTO rules.