Organization for Security & Cooperation in Europe

|  |

Name: Organization for Security & Cooperation in Europe | |

| Acronym: OSCE | |

| Year of foundation: 1994 (1975 as CSCE) | |

| Headquarters: Vienna, Austria | |

| Official web site: go to page | |

| OSCE documents:go to page | |

FOCUS ON | |

| Osce Parliamentary Assembly |

History

The creation of the CSCE

The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe is the final outcome of a process whose foundations were set with the signature of the Helsinki Final Act on August 1st 1975 and the creation of a permanent Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe. Following the Cuba missiles crisis, and the improvement of US-Soviet diplomatic communications, the Conference served the purpose of bringing together the two superpowers, their allies and the non-aligned States during the period of the so called Détente, to resolve common challenges and to work towards the promotion and the maintenance of peace and security in the Euro-Atlantic area.

The way to the Helsinki talks, which began in 1973 and culminated two years later with the adoption of the Final Act, was paved by a series of declarations and official statements, which in practice triggered a process of informal dialogue between East and West. In 1966, the countries of the Warsaw Pact (the mutual defence treaty subscribed by communist States in response to West Germany’s integration to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)), issued the Bucharest Declaration on Strengthening Peace and Security in Europe, which called for a conference between European countries (with the implicit but clear exclusion of the US) with the twofold purpose of confirming the status quo of European borders, on one hand, and promoting cooperation between European countries in the fields of science, technology and culture, on the other. In response to that, in December 1969, the NATO ministerial meeting in Brussels issued a Declaration on European Security that gave a cautious encouraging response to the renewed appeals of the Warsaw Pact for a security conference, adding to the topics to be discussed the focus on the human dimension of security. In the following years, the results of West Germany’s Ostpolitik facilitated the move of both alliances towards the acceptance of the reciprocal requests which finally led to the Helsinki talks.

The Helsinki Final Act was the outcome of a long negotiation process between different groups of States, such as: the Warsaw Pact States which had been supporting the Conference since the 1966 Bucharest Declaration, including the communist States of Eastern Europe (Hungary, Romania and Czechoslovakia) that were worried about Soviet dominance in the region; the western countries of the EC and NATO with the participation of the US and Canada; and neutral States such as Ireland, Switzerland and Sweden. It should be noted that despite the strong influence of the four winning Powers of WW II on the Helsinki process, the success of the latter is based on the acknowledgement by these Powers of the need to engender a different power equilibrium in Europe, one involving a broader range of States. Indeed, the Conference was to “take place outside military alliances” and all countries would participate “as sovereign and independent States and in conditions of full equality”. Negotiations took place during three stages: the preparatory consultations from November 1972 to June 1973 produced (and adopted in July) the “Final Recommendations of the Helsinki Consultations” establishing the rules on the organization of the Conference, the items on the agenda, and other procedural rules; from September 1973 to July 1975 the negotiations phase in Geneva produced the Helsinki Final Act; lastly the Act was signed by the 35 participating States on 1 August 1975. With a long term vision on the multilateral process initiated by the Conference, the participating States enounced in the last part of the Helsinki Final Act – entitled “follow–up to the Conference” – their commitment to continue cooperation in the context of future periodical meetings among their representatives.

It should be noted that one of the defining features of the Helsinki Final Act is that it was not meant to be a legally binding document. The principles and the obligations enounced therein have a high political relevance but not a legal one, that is, they do not give rise to legally enforceable international treaty obligations. This is also confirmed by the fact that the Finnish government was asked not to register the Helsinki Final Act with the UN Secretariat according to art. 102 of the UN Charter, with the consequence that violations of it cannot be invoked before the organs of the United Nations Organization. Considering the fragility and fluidity of the political situation and the final aim of the relaxation of the East-West conflict, the implementation of political “without teeth” solutions was considered a more suitable choice than the adoption of inflexible legal obligations for the participating States. The final outcome was a document that fulfilled the inspirations of the different groups of States involved. From the Soviet perspective, the Conference confirmed the status quo in Europe, while for the US, such confirmation was fully in line with her policy of “containment without confrontation”. The Warsaw Pact States wary of Soviet dominance obtained political assurance of the respect of State sovereignty, and the neutral States could further strengthen their position of neutrality.

The Helsinki Final Act

As is known, the Final Act adopts a comprehensive approach to peace and security, acknowledging the interdependence between military security, economic relations and human rights. It thus identifies three dimensions of cooperation activity of the CSCE and illustrates them in detail in three “Baskets” (according to the curious expression proposed by a Dutch representative) dealing respectively with political and military relations, economic and environmental cooperation and finally, cooperation in the humanitarian and other sectors. The first Basket also comprises a Declaration on Principles Guiding Relations between Participating States in the realization of the cooperation goals of the Conference, also known as the “Decalogue”. Although these principles are presented under the first Basket, some of them have general content and effects and therefore apply also to the areas and sectors comprised under the remaining Baskets.

The majority of the principles enshrined in the “Decalogue” concern the political and military dimension, namely: (i) sovereign equality, respect for the rights inherent in sovereignty; (ii) refraining from the threat or use of force; (iii) inviolability of frontiers; (iv) territorial integrity of States; (v) peaceful settlement of disputes; (vi) non-intervention in internal affairs. The following two principles are focused on human rights and fundamental freedoms and call respectively for (vii) protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief, and for (viii) equal rights and self-determination of peoples. Finally, the last two principles of the Decalogue reflect the general spirit of the Final Act enouncing on the one hand (ix) the need for cooperation among the participating States across the three dimensions of the Conference, and on the other (x) the commitment of States to fulfill in good faith their obligations under international law.

The overlap in the content of some of these principles can be explained by the highly political character of the negotiations of the Final Act within the context of the Cold War. For instance, in the drafting of the first principle, on national sovereignty, negotiations focused on its impact in relation to the third Basket. The position of the Soviet delegation in this regard was to match the achievement of the goals in the human rights and humanitarian sector against the standards established at the national level – rather than against international standards – thus avoiding any interference in domestic affairs. The compromise reached was the separate statement of these interlinked principles. Therefore, while the fist principle affirms that participating States “will (…) respect each other's right freely to choose and develop its political, social, economic and cultural systems as well as its right to determine its laws and regulations”, the seventh principle confirms the commitment of States to constantly respect human rights and fundamental freedoms in their mutual relations and to “endeavour jointly and separately, […] to promote universal and effective respect for them”. The latter principle also recognizes “the universal significance of human rights and fundamental freedoms” and, for the first time in an international document, the fact that respect for human rights “is an essential factor for the peace, justice and well-being necessary to ensure the development of friendly relations” among States. The ten principles of the Final Act have provided a constant guide – yet one adaptable to the historical context – in the cooperation efforts of the participating States to the CSCE/OSCE.

As regards the sectors of cooperation covered by the Helsinki Final Act, besides the Declaration of principles, the first Basket, on the politico-military dimension, contains a series of recommendations concerning voluntary measures aimed at implementing the principle of abstention from the threat or use of force, including through the elaboration of a new system for the peaceful settlement of disputes. Basket I also sets out measures finalized at increasing confidence and fostering security building among participating States in a spirit of transparency, by means of notification of military maneuvers and voluntary exchange of observers at such maneuvers. These recommendations have set the basis for the establishment of “a regime for the democratic control of armed forces” which has been further improved in the course of time. The economic dimension detailed in Basket II includes recommendations on the promotion of commercial exchanges through the reduction of barriers to trade, on industrial cooperation, on collaboration in the fields of agriculture, energy, space research and medicine with a specific focus on science and technology, and finally, on measures for addressing a transnational problem such as environmental pollution. The provisions of the second Basket are followed by a series of recommendations on cooperation with non participating Mediterranean countries in order to promote and strengthen security in this area. Basket III focusing on democratization and human rights represents to date the most performing and effective dimension of cooperation within the OSCE. However, it should be noted that while these aspects were only generically addressed in the Helsinki Final Act – mainly in terms of familial and social exchanges and exchange of information in the cultural and educational sectors – a strong focus has been placed since the end of the Cold War on fundamental human rights, the protection of vulnerable groups and the promotion of the rule of law.

In its last part, the Helsinki Final Act established the rules for a follow-up on the Conference through periodic meetings in order to continue the dialogue under each of the three dimensions. Follow-up meetings on the Conference have taken place in Belgrade (1977-1978), Madrid (1980-1983) and Vienna (1986-1989), and additional ad-hoc workshops and conferences have taken place among the participating States. Such meetings generally integrated three components: the review of the implementation of the undertaken commitments, the consideration of new proposals for reform and the adoption of a concluding document. Therefore, over the years, in order to respond to the changing nature of security challenges in the Euro-Atlantic area, the Conference went through important institutional reforms and gradually strengthened its focus on the human dimension of security. Following the path set by the adoption of a politically-, but not legally-binding agreement, the participating States that adopted the Final Act chose once again a “soft” and flexible model for future cooperation. However, despite their political character, the principles and commitments set out in the Final Act had the potential of directly influencing the system of legal relations between States as well as the single legal systems in the Euro-Atlantic area, and after the end of the Cold War the establishment of a permanent institutional structure became necessary. In some cases, such as in the areas comprised in the second dimension, the principles and commitments enshrined in the Final Act served as “a political ‘catalyst’ for the activities of more specialized and endowed organizations”.

From the CSCE to the OSCE

With the relaxation of the political relations in the Euro-Atlantic area in the late 1980s, the participating States to the CSCE were compelled to re-assess the status of peace and security in Europe and the role of the Conference in that regard. The transition from conference to organization is a corollary of this acknowledgement and it was anticipated by a series of conferences, meetings, seminars and action plans which defined with a clearer focus the objectives of the future Organization and set up its institutional basis.

As it was anticipated, the awareness of the interdependence link between security on the one hand and human rights, democracy and the rule of law on the other was the inspiring principle at the basis of the Helsinki Final Act. Over the years, the CSCE progressively deepened and broadened the human dimension of security defined in the third basket and this process came along with the expansion of the representative basis of the Conference to cover the new independent States resulting from the disintegration of the Soviet Union and of Yugoslavia. The First Meeting on the Human Dimension of the CSCE held in Paris in 1989 and followed up in Copenhagen the next year represents a clear example of this focus shift in the nature of cooperation and security in Europe. This is further confirmed in the Charter of Paris for a new Europe, adopted at the conclusion of the Paris Summit in 1990, which clearly states that the change in the political environment has engendered “a new era of democracy, peace and unity” in Europe. In order to face the new challenges of the post-Cold War era, such as State collapse, stalled transitions to democracy and protection of minorities, participating States reaffirm in the Charter of Paris the permanent validity of the ten principles enshrined in the Final Act, but they also “resolve to give a new impetus” to co-operation setting out the necessary procedures and institutional arrangements to that end in a supplementary document. OSCE’s key institutions such as the Council of Ministers for Foreign Affairs, a permanent Secretariat in Prague (now based in Vienna but assisted by an office in Prague), the Conflict Prevention Centre (CPC) based in Vienna and the Office for Free Elections based in Warsaw were established in that occasion. This gave thrust to the gradual transformation, from 1990 to 1994, of the conference into an organization. In particular, the 1992 Helsinki Summit was crucial in such process. Attention focused not only on the review of the implementation of CSCE commitments, in particular of those concerning human rights and the human dimension, but above all on the appraisal of the operational record of the newly established institutions and on how to increase their effectiveness and incisiveness. Therefore, when the members of the Conference officially confirmed in the Budapest Summit Declaration the name change, guided by their determination “to give a new political impetus to the CSCE, thus enabling it to play a cardinal role in meeting the challenges of the twenty-first century”, the great part of the administrative and institutional structure of the organization had already been established. This decision took effect form 1 January 1995.

However, the overall structure of the OSCE is different from other “standard” international organizations. Continuing the flexibility trend of the Helsinki Final Act, the new organization has maintained in place several mechanisms of institutional and organizational ambivalence, which validate its classification as a “soft organization”. In the first place, the context driven institutional growth of the OSCE explains its rather intricate structure of institutions and bodies. The lack of a charter or a founding treaty coupled with the political nature of the commitments undertaken by participating States have developed a vast amount of norms, principles and commitments - especially in the area of human security – with no clearly discernible hierarchy (the so called OSCE acquis). Of course the ten principles enounced in the Helsinki Final Act can be considered as the founding principles at the basis of all activities of the Organization but it should be noted that even though they are closely related to international customary or treaty-based principles they lack legally binding force. At most, by reason of their political incisiveness, the commitments undertaken by participating States can be considered soft law. OSCE’s ambivalent character is confirmed also in relation to the lack of a well integrated and balanced institutional structure. Thus, on the one hand, the political institutions play a predominant role within the OSCE, while on the other, institutions such as the High Commissioner on National Minorities and the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights enjoy a broad autonomy within the organization.

Finally, another element of flexibility that characterizes the OSCE is the issue of its legal capacity. It should be noted that para. 29, chapter 1 of the Budapest Decisions (“Strengthening the CSCE”) provides that “The change in name from CSCE to OSCE alters neither the character of our CSCE commitments nor the status of the CSCE and its institutions”, but it also adds that “In its organizational development the CSCE will remain flexible and dynamic”. The OSCE can certainly be identified as an international organization. Its organs operate on the basis of their own system of rules, including procedural ones, striving to achieve the common objectives identified by participating States, but “it lacks any significant legal capacity under international law”. Such issue has been debated since the 1992 Stockholm Ministerial Council and an Informal Working Group on Legal Capacity has been established but no consensus has yet been reached. Nor did the recommendations made at the 1993 Rome ministerial Council, concerning the conferral of legal capacity to the organization by each participating State on the basis of domestic law have any sequel. While the issue of the need to confer legal capacity to the OSCE is not under discussion, States disagree on the extent of privileges and immunities deriving for the organization and its organs from such attribution. In the absence of such legal capacity, the acts of the organization cannot be attributed to it as an international subject, distinct from participating States, and no international agreements can be stipulated between the organization and a participating State, for instance for the establishment of an OSCE mission on the territory of the latter.

OSCE's activity in recent years

In the second half of the 1990s OSCE actively participated alongside other regional and international organizations in the efforts to guarantee security and to restore political, social and economic equilibrium in the region. Its activities were focused on the one hand on conflict prevention and security, and on the other, on the promotion of democracy and human rights, closely combining these two aspects.

After its rapid institutionalization, which as earlier noted took place between 1991 and 1994, in the second half of the 1990s the OSCE got involved in three main groups of activity. Firstly, it played a crucial role in conflict prevention and stability reinstatement in the Balkan area. Thus, in 1995, with the end of the war in Bosnia Herzegovina, the Dayton Accords entrusted the OSCE, alongside other organizations, with the task to monitor, oversee, and implement components of the agreement. To carry out its mandate under the Accords, the OSCE established and successfully administered a mission for organizing free elections in Bosnia and Herzegovina. A post war rehabilitation mission was established in Croatia in 1996, and a field presence was set up in Albania the following year to deal with the social unrest set in motion by the financial pyramid schemes’ crisis. Moreover, when the violent conflict in Kosovo broke out in 1998, Serbia agreed to accept an OSCE Verification Mission for Kosovo, which would have monitored compliance with the peace conditions established by the UN Security Council. After the conflict, the OSCE established a new Mission to Kosovo (OMIK) under the supervision of the UN Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK).

Secondly, the OSCE got also involved in a series of field missions and assistance activities in South Caucasus and Central Asian countries. It thus sent out in 1995 an assistance group to Chechnya and opened a liaison office for Central Asia in Uzbekistan (Tashkent). Later in 1998, an advisory and monitoring group was dispatched to Belarus and OSCE centers were opened in Kazakhstan (Almaty), Turkmenistan (Ashgabat), Kirghizstan (Bishkek) and Tajikistan (Dushanbe).

Thirdly, in the years that immediately followed its institutionalization, the OSCE tried to strengthen its position as a crucial regional actor for security and stability in Europe by actively cooperating with the other regional organizations, namely NATO, CoE and EU. As a completion of its engagement in field missions and assistance in the Balkans and in the former Soviet republics, the OSCE became the repository of the Pact on Stability in Europe adopted at the initiative of the EU in 1995, and was entrusted with its monitoring. In June 1999, another initiative of the EU, the Stability Pact for South Eastern Europe, was “placed under the auspices of the OSCE” which involved full reliance on “the OSCE to work for compliance with the provisions of the Stability Pact by the participating States, in accordance with its procedures and established principles”. Acknowledging that concerted action between the different organizations operating in the region would have strengthened the role of the OSCE by reaping important benefits from its peculiar features, at the Istanbul Summit in November 1999 the Platform for Co-operative Security was adopted, a document that delineates the principles and procedures for working together with other international and regional organizations.

By the time of the beginning of the new century the crises following the break up of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union in which OSCE had been involved in the 1990s had either been resolved, for the major part, or were at a stalemate and their resolution would not have been imminent. Therefore, part of the assets – in terms of institutions, missions, monitoring groups and assistance programs – developed and put into test by the OSCE in the previous decade had to be reshaped in order to adequately meet the challenges related to the changed focus from conflict-related emergency interventions to broader long term missions combining the different dimensions of security. This acknowledgement clearly emerges in the Charter for Security in Europe adopted at the last OSCE Summit held in Istanbul in 1999, in which participating States enounce their commitment to “develop and strengthen this instrument [field operations] further” in order to carry out tasks which may, include “assisting in the organization and monitoring of elections; providing support for the primacy of law and democratic institutions and for the maintenance and restoration of law and order; helping to create conditions for negotiation or other measures that could facilitate the peaceful settlement of conflicts (…)”. The same principle is further reconfirmed by the 2003 ministerial Council in 2003, in the OSCE Strategy to Address Threats to Security and Stability in the Twenty-First Century. It is recognized that “[t]hreats to security and stability in the OSCE region are today more likely to arise as negative, destabilizing consequences of developments that cut across the politico-military, economic and environmental and human dimensions, than from any major armed conflict”. In the same document, terrorism is identified as “one of the most important causes of instability in the current security environment” requiring “a global approach, addressing its manifestations as well as the social, economic and political context in which it occurs”. Organized crime, practices related to discrimination and intolerance and deepening economic and social disparities constitute according to the Ministerial Council additional factors affecting security and stability in the OSCE region. To deal with such a changing security environment in which threats constantly evolve, the OSCE Strategy to Address Threats to Security and Stability in the Twenty-First Century puts emphasis on the Annual Security Review Conference (ASRC) established by the 2002 Porto Ministerial Council, as a dialogue forum for identifying, analyzing and reacting to new threats as they emerge.

Preparing to face the new security environment, in recent years the OSCE has been confronted with an identity crisis putting its relevance into question. The compound character of OSCE field missions touching upon each of the domains in which the organization is involved, coupled with the particularly good performance of the OSCE under the third basket have led to criticism by some delegations on the unbalanced development of the three dimensions of the OSCE (with an “overemphasis on the human dimension”) and on geographically ‘biased’ field operations. The low visibility of the organization and the lack of clearly established ‘rules of the game’ constitute additional elements of weakness of the organization. In response to such criticism, the report issued in 2005 by a panel of eminent persons tasked to review the effectiveness of the OSCE and to recommend reform measures identifies three sets of problems at the basis of the crisis faced by OSCE: the uneven pace of integration, economic growth and democratic development in the OSCE region which has led to the emergence of new problems in achieving comprehensive security; the enlargement of the other regional actors, such as the European Union and NATO, which has challenged the role of the OSCE as a regional arrangement under Chapter VIII of the UN Charter; finally, the lack of a clear status which has obfuscated the organization’s profile and identity thus hindering the OSCE from becoming a full-scale regional organization. These problems are also highlighted in other proposals for reform. All of them place the focus on the need to strengthen OSCE’s identity and profile through a structural response aimed on the one hand at ensuring a balanced development of the three dimensions and the equal applicability of all OSCE commitments to all participating States, and on the other at reducing the ambiguity and political marginalization of the OSCE by insisting on its comparative advantages and the added value it can yield by comparison to other organizations.

Governance structure and decision-making procedures

As the result of a rapid institutionalization process at the beginning of the 1990s, a wide set of institutions and bodies build up today the complex organizational structure of the OSCE. It comprises: all-purpose decision-making bodies such as the Summits, the Ministerial Councils and the Permanent Council, and decision making bodies that operate within their field of competence such as the Forum for Security Cooperation (FSC); operational institutions such as the OSCE Secretariat, the Chairman-in-Office (CiO) and the Troika mechanism, the personal representatives of the CiO, OSCE missions and other field activities, the Economic and Environmental Forum and the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly; specialized operational bodies under the third dimension such as the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, the High Commissioner on National Minorities, the Representative on the Freedom of the Media; and other OSCE related bodies such as the Court of Conciliation and Arbitration.

The rules for decision making agreed over time have been codified in the Rules of Procedure of the OSCE, adopted by the Brussels Ministerial Council in December 2006. This document makes a basic distinction between OSCE official bodies, “which are authorized to take decisions and adopt documents having a politically binding character for all the participating States or reflecting the agreed views of all the participating States”, and other OSCE bodies which should be regarded as informal bodies. It further clarifies that “documents issued by the Chairpersons of OSCE decision-making bodies or by OSCE executive structures shall not be regarded as OSCE documents and their texts shall not require approval by all the participating States”.

In general, it can be noted that, with some exceptions, OSCE’s organizational structure is characterized by the lack of a clear hierarchical relationship between the different institutions and by the different visibility and achievements of the institutional resources operating under each of the three dimensions.

OSCE Summits and Ministerials Councils

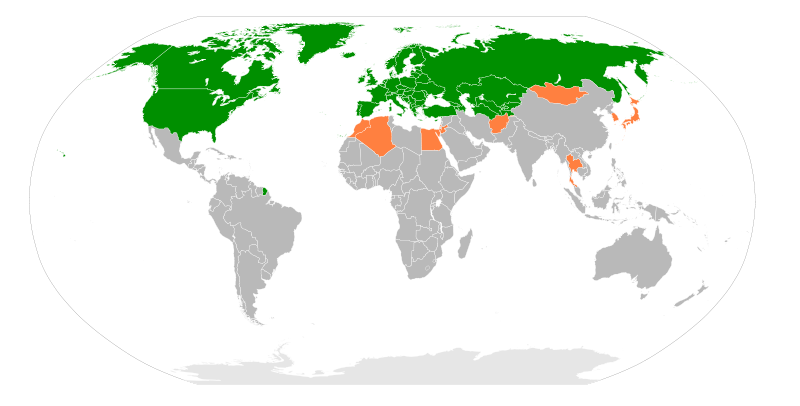

Summits are periodic meetings of Heads of State or Government of the 56 OSCE participating States. It is the highest all-purpose decision making body of the OSCE which sets the political priorities for the organization. OSCE summits are also open to the Mediterranean and Asian Partners for Cooperation, other international organizations and non governmental ones. The Helsinki final Act was signed during the first OSCE summit in 1975 and, since then, the Meetings of Heads of State or Government have scanned the process of the transformation of the CSCE into the OSCE. The fundamental document of the CSCE, the Helsinki Final Act, was adopted by the original 35 participating States at the first Summit of the Conference, while at the second CSCE Summit, held in Paris in 1990, the foundations of the institutionalization process were laid. Although participating States agreed at the 1992 Helsinki Summit to continue meeting every two years no OSCE Summits have been organized since 1999. For this reason OSCE Summits seem to reflect the political legacy of the CSCE and do not fully meet the needs of a permanent organization.

During periods between Summits, decision-making power is exercised by the Ministerial Council (formerly Council of the CSCE), which consists of the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of participating States. The Council meets once a year towards the end of the term of the chairmanship and its role is to maintain a link between the political decisions taken at the Summits and the every day functioning of the Organization. However, considering that no Summits have taken place in the last decade, the Ministerial Council has in practice become the pivotal political decision-making body providing guidance to the organization. The Ministerial Council has the authority to determine and direct the work of the other OSCE bodies, which in turn are responsible towards it. The Ministerial Council acts as a negotiation forum in which the Foreign Ministers make statements and the Mediterranean and Asian Partners for Co-operation or other international organizations are involved in consultations. Additionally the Ministerial Council receives and discusses formal reports, and approves documents that have been adopted by the Permanent Council or the Forum for Security Co-operation (infra).

As regards decision making procedures, it has already been noted that OSCE decisions are generally adopted by consensus and that they are politically but not legally binding. All OSCE participating States are put on the same level and act in conditions of full equality. The OSCE Rules of Procedure explain that consensus “shall be understood to mean the absence of any objection expressed by a participating State to the adoption of the decision in question”. The same document clarifies that the texts referred to as ‘OSCE decisions’ or ‘OSCE documents’ are characterized by the fact that they have been adopted by a decision-making body by consensus, independently from the formal name of the document - “decisions, statements, declarations, reports, letters or other documents”. States are allowed to make formal reservations or interpretative statements on given decisions and may ask the Secretariat to register and circulate them to the participating States, but these do not block the adoption of the decision.

There are however three prominent exceptions to the consensus rule. Apart from the majority rule on the basis of which recommendations are adopted by the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly (see infra), the other exceptions imply the exclusion of certain participating States from the adoption by consensus of the decision. The so called “consensus minus one” procedure was formulated in the Prague Document on Further Development of CSCE Institutions and Structures adopted at the CSCE Council in January 1992. The exception, which has been invoked to suspend Yugoslavia from the CSCE later in the same year, implies that in cases of a State’s “clear, gross and uncorrected violation” of CSCE commitments, decisions may be taken without the consent of the State concerned. The second exception, referred to as “consensus minus two” procedure, was adopted at the CSCE Council in Stockholm in December 1992. It concerns the peaceful settlement of disputes and enables the Ministerial Council to direct two participating States that are in dispute to seek conciliation, regardless of whether or not they agree to settle the dispute by means of conciliation.

The Permanent Council

The Permanent Council (PC) is the body for regular political consultation and decision-making on all issues of OSCE competence. It was first created as the “Council of Senior Officials” under the Charter of Paris (1990), then transformed into the “Permanent Committee” at the Rome Ministerial Council in 1993, finally becoming the “Permanent Council” when the CSCE was renamed the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. The permanent representatives of the participating States chaired by the permanent representative of the State holding the Chairmanship of the OSCE meet weekly in Vienna to discuss and set the operational agenda of the organization. For instance, they negotiate and take decisions on the deployment of missions and field operations, on the budget, on the establishment of informal subsidiary bodies, etc.

The work of the Permanent Council is supported and organized by the Preparatory Committee, established by the 1999 Istanbul Summit. The Committee meets in informal format and has to report back to the Council. Sessions with a sectoral focus are prepared by other subsidiary bodies such as the Advisory Committee for Management and Finance, the Contact Group with the Mediterranean Partners for Co-operation or the Contact Group with the Partners for Co-operation in Asia. Upon the suggestion of the Panel of Eminent Persons on Strengthening the Effectiveness of the OSCE, at the 2006 Ministerial Council in Brussels, it was decided to establish three informal subsidiary bodies of the Permanent Council reflecting the different security dimensions of the OSCE: a Security Committee, a Human Dimension Committee and an Economic and Environmental Committee. These bodies contribute to formulating OSCE policy but they cannot adopt binding decisions.

The Permanent Council acts therefore as an important forum for continuous dialogue among OSCE participating States. However it should be noted that Permanent Council meetings are not open to the public, even though it may be arranged that young diplomats, academics, students, and other groups with an interest in the OSCE observe the meetings. Moreover, meetings of the Preparatory Committee in which real spontaneous dialogue takes place during the informal consultations are always off the record.

Forum for Security Cooperation (FSC)

The Forum for Security Cooperation (FSC) is a separate decision-making body in the area of military security and stability, established by the Helsinki Summit Document in 1992. The FSC holds regular weekly meetings in Vienna in which participate members of the delegations of OSCE States that work in the Permanent Council. It thus allows the Permanent Council to meet to discuss politico-military issues specifically. The FSC is chaired by a representative of a participating State designated by rotation every four months and by analogy with the OSCE Troika, the Chairman of the FSC is assisted by the incoming and the outgoing Chairmen. Besides strengthening cooperation and facilitating information exchange on matters related to security, the FSC has negotiated different political agreements on arms control, disarmament and confidence- and security-building, and upon request, provides assistance to participating States in implementing the agreed measures.

OSCE Secretariat

The OSCE Secretariat, located in Vienna and assisted by an office in Prague, provides administrative support to decision-making bodies. It also maintains an archive of CSCE/OSCE documentation and circulates documents as requested by the participating States. The Secretariat is placed under the direction of a Secretary General who is the chief administrative officer of the Organization and acts as a representative of the Chairman-in-Office. Strengthening the role of the Secretary General so as to counterbalance the discontinuity of annually changing Chairmanships is one of the themes on OSCE reform enjoying strong support by participating States. The Secretary General is appointed by the Ministerial Council for a three years term, renewable once, and is accountable to it. The post of OSCE Secretary General has been held since June 2005 by the Ambassador Marc Perrin de Brichambaut of France.

In order to provide support to the activity of decision making bodies in the different issue areas of competence of the organization, the Secretariat comprises an articulated structure of issue-specific units and departments. These include among others: the Conflict Prevention Centre providing support for the Chairman-in-Office and other OSCE decision-making bodies in matters such as early warning, conflict prevention, crisis management, and post-conflict rehabilitation; the Action against Terrorism Unit assisting participating States in drafting legislation and monitoring the impact of anti-terrorism measures on human rights as well as in implementing the different international conventions and protocols related to the fight against terrorism; the Anti-Trafficking Assistance Unit helping the Chairman-in-Office Special Representative and Co-ordinator for Combating Trafficking in Human Beings in fulfilling his/her multi dimensional mandate which touches upon human rights and the rule of law, law enforcement, inequality and discrimination, corruption, economic deprivation and migration; the Office of the Co-ordinator of OSCE Economic and Environmental Activities providing support on issues concerning economic, social and environmental aspects of security; the OSCE's Strategic Police Matters Unit which contributes in building up police capacity in several countries in South-Eastern Europe and Central Asia, including multi-ethnic police forces; and the Section for External Co-operation supporting the Secretary General, the Chairmanship and participating States in dialogue and co-operation with Partner States and in maintaining institutional co-operation with partner organizations.

The Chairman-in-Office (CiO) and the Troika mechanism

The Chairman-in-Office bears overall responsibility for executive action, provides the political leadership of the OSCE by setting its priorities during the year in office and is responsible for the external representation of the organization. Established when the Conference was renamed as an “organization” most of the powers of the CiO are based on unwritten customary rules developed in the praxis of the organization. The OSCE Chairmanship is held for one calendar year by an OSCE participating State designated by a decision of the Ministerial Council. The function of the Chairperson-in-Office is exercised by the Minister of Foreign Affairs of that State. The current Chairman-in-Office is Kazakhstan's Secretary of State and Foreign Minister Kanat Saudabayev. The Chairman is assisted by the previous and succeeding Chairpersons and the three of them constitute the Troika. This latter institution thus ensures a certain level of political consistency at the higher political representative levels at the OSCE. The activities of the Chairman include dictating an agenda for the OSCE, preparing and chairing meetings of the Summit and Ministerial Council, taking the initiative in implementing Ministerial Council decisions, making statements on behalf of the Organization, and providing political guidance to field operations.

The Personal Representatives of the CiO

In order to ensure a better coordination of its multiple responsibilities the Chairman-in-Office may appoint, for the duration of the term of office, personal or special representatives with specific tasks related to definite thematic sectors or certain geographical areas. In some cases, however, the mandate of the special representatives has been renewed from one chairmanship to the other.

The present Chairman-in-Office has appointed three Personal Representatives to Promote Greater Tolerance and Combat Racism, Xenophobia and Discrimination, respectively, against Jews, Muslims and Christians and members of other religions. In addition, the current CiO has appointed Representatives to deal with conflict prevention issues in specific geographic areas, namely the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Moldova and Central Asia, a personal Representative on the OSCE Minsk Conference tackling the issue of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, and two personal Representatives for the Dayton Accords (the General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina).

The Economic and Environmental Forum

The Economic and Environmental Forum is a highest level annual meeting within the economic and environmental dimension of the OSCE organized by the Office of the Co-ordinator of OSCE Economic and Environmental Activities at the Secretariat. The numerous (more than 400) participants to the Forum, which comprise representatives of governments, civil society, the business community and international organizations, exchange their views and try to identify viable solutions to problems related to the specific theme proposed each year by the Chairmanship and agreed upon by the 56 participating States. The role of the Forum is to give political stimulus to the dialogue on economic and environmental issues as one of the dimensions of security and to suggest specific recommendations and follow-up activities to address these challenges. The Forum also reviews the implementation of the participating States' commitments in the economic and environmental dimension.