North Atlantic Treaty Organization

| |

Name: North Atlantic Treaty Organization | |

| Acronym: NATO | |

| Year of foundation:1949 | |

| Headquarters: Brussels, Belgium | |

| Official web site: go to page | |

| NATO documents: go to page | |

FOCUS ON | |

| NATO Parliamentary Assembly |

Description

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO; French: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique Nord - OTAN) is an intergovernmental military alliance which constitutes a system of collective defence whereby its member States agree to mutual defence in response to an attack by any external party.

Member States

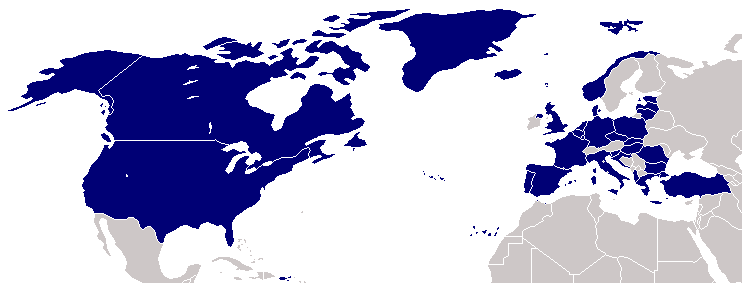

NATO has 28 member states, namely:

Date | Country | Enlargement | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 April 1949 | Founding Countries | ||

| In 1966 France unilaterally withdrew from NATO's integrated military command. Since that year France participated only into the political structure and its Armed Force were reintegrated only after the official announcement in 2009. | |||

| Iceland is the only NATO member that maintains no standing army and joined the alliance under the condition of creating it. However, it has a Coast Guard and recently provided troops in Norway for NATO peace-keeping missions. | |||

| 18 Febraury 1952 | First Enlargement | In 1974, as a consequence of the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, Greece withdrew its forces from NATO’s military command structure but, with Turkish cooperation, were readmitted in 1980. | |

| 9 May 1955 | Second Enlargement | As West Germany. Saarland unified in 1957, while West Berlin and East Germany were reunified on 3 October 1990. | |

| 30 May 1982 | Third Enlargement | Only in 1998 Spain entered into military structure. | |

| 12 March 1999 | Fourth Enlargement | ||

| 29 March 2004 | Fifth Enlargement | ||

| 4 April 2009 | Sixth Enlargement | ||

Brief History

The origins of NATO are difficult to determine with any degree of certainty. The late 19th century offered unprecedented levels of transatlantic diplomatic co-alignment in diplomatic and military arena; however, vitally shared interests from the first two world wars would be required for concrete amiability to emerge from this “Great Rapprochement.” By 1941 the ‘Atlantic Charter’ effectively erased any lingering questions regarding the significance of Euro-Atlantic security. The end of the Second World War brought the fall of one threat to the security of Western Europe but with it, the rise of another. The development and use of the world’s first atomic weapons, the failure of the League of Nations, and the creation of the United Nations were all indicators that the world was becoming increasingly more transnational and interconnected. Technological advancements coupled with unprecedented levels of interdependence and interconnectivity had effectively extinguished the possibility for nations to achieve domestic security through isolationist policies.

The Creation of NATO

The Treaty of Brussels, signed on 17 March 1948 by Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, France and the United Kingdom is considered the precursor to the NATO agreement. The treaty and the Soviet Berlin Blockade led to the creation of the Western European Union's Defense Organization in September 1948. However, participation of the United States was thought necessary in order to counter the military power of the USSR, and therefore talks for a new military alliance began almost immediately.

These talks resulted in the North Atlantic Treaty, which was signed in Washington, D.C. on 4 April 1949. It included the five Treaty of Brussels states, as well as the United States, Canada, Portugal, Italy, Norway, Denmark and Iceland. Popular support for the Treaty was not unanimous; some Icelanders commenced a pro-neutrality, anti-membership riot in March 1949. While the original signatories of the North Atlantic Treaty were clearly in search of a mechanism to “keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down” (The Origins of the Cold War in Europe: International Perspectives, edited by David Reynolds, New Haven-London, Yale University Press, p. 13), this pact of collective security was also an instrument to codify a set of intrinsic values, shared by all 12 nations.

NATO during the Cold War

The beginning of the Korean War in 1950 was decisive for NATO as it showed the apparent threat level greatly and obliged the organization to develop concrete military plans: at the 1952 Lisbon conference, the post of Secretary General of NATO as the organization’s chief civilian was also created. In the same year, the first major NATO maritime exercises began.

In 1954, Moscow declared that it should join NATO to preserve peace in the Old Continent. The proposal was rejected, since NATO member-states feared that the Soviet Union’s motive was to weaken the alliance. As a formal response, the Organization of the Warsaw Pact (14 May 1955) was created.

Three years later, the new French President Charles de Gaulle De Gaulle protested at the United States' strong role in the organization and what he perceived as a “special relationship” between the United States and the United Kingdom and asked both the creation of a tripartite directorate that would put France on an equal footing with the United States and the United Kingdom, and an expansion of the organization to geographical areas of French interest, specifically to Algeria. Considering the response given to be unsatisfactory, de Gaulle began to build an independent defense for France. In 1966 France unilateralli withdrew from NATO's integrated military command. Paris remained a member of NATO, but the headquarters of the alliance were moved form Paris to Mons, Belgium, in 1967.

During most of the Cold War, NATO maintained a holding pattern with no actual military engagement as an organization. On 1 July 1968, the signature’s procedure of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty started: NATO declared that its nuclear sharing arrangements did not breach the treaty as U.S. forces controlled the weapons until a decision was made to go to war, at which point the treaty would no longer be controlling.

NATO after the Cold War

The original commitment to the principles of democratic liberalism through the strengthening of free institutions has continued though the institution’s 62 years and continues to be the backbone upon which organizational policies and actions are decided. Changes in the post-Cold War international environment shifted NATO’s priorities away from European stability through collective security with from a Russian threat.

Currently, NATO pursues European stability largely through the promotion of political cooperation and the process of democratization, especially in former Soviet-bloc countries. As NATO’s historical adversary abated with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the institution began to enjoy greater freedom and geographical range in the promotion of liberal democratic tenets.

NATO’s Enlargements

The accession process to NATO membership has evolved from the 1952 expansion to the most recent 2009 induction. In 1952 Greece and Turkey joined NATO, and West Germany was incorporated on 9 May 1955. On 30 May 1982, NATO gained a new member when, following a referendum, the newly democratic Spain joined the alliance. In 1999, three former communist countries, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland joined the organization, which accepted also Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Romania on 29 March 2004. At the April 2008 Summit in Bucharest, NATO agreed to the accession of Croatia and Albania and invited them to join. Both countries joined NATO in April 2009. At the 2008 Summit, three countries were promised future invitations: the Republic of Macedonia, Georgia and Ukraine. Other potential candidate countries include Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina, which joined the Adriatic Charter of potential members in 2008.

Many of former Soviet-bloc countries that sought and gained NATO membership between 1999 and 2004 did so, in large part, in an attempt to procure security against a Russian military threat. The collective security that NATO offered can be seen as a means to assuage the military concerns of member countries, which may allow an increased focus on national political and economic development, key components to a successful and stable democracy. In a number of these newly autonomous states, the military was viewed as one of a very limited number of stable governmental institutions. Facing national fractionalization, military establishments in this region tended to privilege security over public representation.

NATO Structure and Decision-making Procedures

The North Atlantic Council (NAC)

Like any alliance, NATO is ultimately governed by its 28 member states. Each NATO member state is represented at the organization’s primary decision making body, the North Atlantic Council (NAC) by a nationally appointed Permanent Representative or Ambassador. The NAC meets on a weekly basis at the Ambassador or Permanent Representative level; though, the Council has the flexibility to meet as often as is deemed necessary. The NAC also convenes at the Ministerial level (for both Ministers of Defense and Foreign Affairs) twice a year and, as necessary, at the Summit level, which acts as a forum for discussions between Heads of State of member-nations. The North Atlantic Council is the only institutional body specifically outlined by the Washington Treaty; under the direction of the Secretary General, the NAC has the authority to establish additional subsidiary bodies (generally committees) in order to most effectively implement the principals of the NATO treaty. In an effort to facilitate organizational transparency, the Senior Political Committee is charged with preparing publicly accessible (unclassified), official Council declarations and communiqués, which outline and explain the institutional policies and decisions produced by the NAC process.

Additionally, each member delegation is represented at every level of the committee structure in the fields of NATO activity in which they participate. This system was meant to ensure that the interests of all members would be represented throughout the consultation and decision making processes. At the member-state level, the organizational structure of NATO appears to adhere to the democratic principle of full representation. The mechanism of state representation ensures that the policies and actions of the institution take into account the interests of all members; however, the organizational structure lacks an apparatus that ensures the decisions agreed upon at the NAC are representative of the interests of the citizens who make up the member-states. Direct participation by the citizenry is uncommon in the realm of international diplomacy (particularly within multilateral military institutions); however, individuals of each NATO country are excluded from participation in the decision making process of the institution while bearing an extremely indirect role in the appointment of national representatives to the Alliance. While this organizational structure is far from unique it appears to be somewhat at odds with NATO’s explicit commitment to promote the principles of representative governance.

Executive - NATO Secretary General

NATO’s organizational structure does include conspicuous as well as veiled elements of the qualitative macro indicators pursuant to the international democratic standard. The presence of an Institutional Executive, the NATO Secretary General, provides evidence that this international body represents more than a loose compilation of national actors connected exclusively by organizational functionalism. The existence of a member-appointed institutional leadership position exhibits the willingness of member states to submit to an aspect of internationally representative institutionalism. The NATO Secretary General is afforded with a number of practical responsibilities, including Chairmanship of the North Atlantic Council (retaining the authority to present subjects to the NAC for discussion), the Defense Planning Committee, and the Nuclear Planning group. The Secretariat also plays a large role in NATO partnership councils, chairing the NATO-Russia Council, the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council, and the Mediterranean Cooperation Group. The acting executive of the organization is also holds the authority to offer his “good offices” in an act of arbitration in the event of a dispute between national representatives of member states. Additionally, the Secretary General enjoys ultimate authority on the appointment of NATO-International Staff, as well as acting spokesman for external and international institutional communication. This last charge is particularly important as it represents the acceptance of member-state inclusion into a collective voice of the multinational institution, in the form of an organizational executive acting as an individual spokesman.

Military Command Structure

It is composed by: Military Committee (MC), Chairman of the Military Committee, Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR), Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic (SACLANT), Allied Command Operations, ACO, Allied Command Transformation, ACT.

Throughout the NATO process, sovereignty is paramount. However, once the decision has been made for institutional, military action, and participating members commit military personal and resources to the operation, (following NATO Defense Planning Procedures-essentially based on individual state interest and capability) a large degree of autonomy over those resources is submitted to the Institution’s hierarchical Unitary Command Structure. For the duration of the multinational operation, participating national military resources remain under the command of Allied Command Operations (NATO’s military operations command body), which is responsible to the NATO Military Committee. Upon completion, national military resources committed to the operation are reintegrated into respective domestic military command structures.

NATO’s Integrated Command Structure underwent a significant renewal process as part of the 2002 Prague Summit. Before this point, operational command responsibilities for NATO missions were shared by Allied Command- Europe and Allied Command- Atlantic; since 2003 these two institutional bodies have been restructured into Allied Command Operations, responsible for military operations aspect, and Allied Command Transformation, responsible for future NATO capabilities through guided organizational adaptation. Prior to 2003 troop-generation for NATO missions had been achieved through a process that amounted to organizational ad hocism. Since 2003, the Alliance has hosted an annual ‘Global Force Generation Conference’ to assess national military capabilities of its member states. This conference, in combination with the submission of annual Country Chapters and the ubiquitous inter-member-state military oversight, culminates in the Military Committee’s annual General Report, intended to assess the degree to which nations have fulfilled their respective ‘Force Commitments’ for the previous year. While further contributing to the ideals of institutional military transparency, this process continues to lack a collective mechanism for the castigation of member-states that are found to be delinquent on their professed institutional obligations.

Although the post-2003 operations aspect of the Integrated Command Structure sharpened through additional institutional military capabilities and greater unity of command under the Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR), strategy-formation ultimately remains in the multilateral hands of the North Atlantic Council.

Decision-Making

The decision-making process of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, based on consensus, privileges national sovereignty by effectively giving every member a veto right. In practice however, states may agree to go against national interests in order to align more fully with the will of: the organization, the majority of its members, or its leading nations. This potential scenario may be actualized through the extensive and ubiquitous consultation process that precedes nearly all organizational decisions. The unending consultation between NATO representatives provides a level of inter-member transparency which allows states to more accurately judge respective opinions on a given issue. This process acts as the antithesis of a secret ballot system and allows member states to adjust and harmonize national opinion in accordance with what is perceived to be the prevailing opinion of the institution.

Members also have the opportunity to concede a certain amount of national sovereignty to the organization through the “Silence Procedure.” This term describes a process by which the NATO Secretary General distributes a referendum or resolution outlining an organizational action or policy scheduled for implementation, conditional on the absence of explicit member-state-objection. To voice an objection a national representative would be forced to “break silence,” halting the enactment process. This is a well documented but unofficial NATO decision making procedure that ostensibly assumes member agreement unless the opposite opinion is expressed. The practice provides an opportunity and, to some extend, an incentive for member countries to act in accordance with what can be viewed as the collective will of the institution. It is not difficult to imagine a scenario in which no country is willing to halt a silent referendum and risk the stigma of breaking silence against what appears to be the shared will of all other member states. Taken further, one could imagine that as the deadline for protest approaches and silence is maintained, a potential objector to the proposal would surely begin to assume collective institutional agreement on the given issue and therefore be even less likely to risk national isolation through protest. The constant consultative process as well as the “Silence Procedure” offers the potential for member countries to relinquish a degree of autonomy to the collective will of the organization. The repeat-contact between Permanent Representatives undoubtedly creates an environment that discourages recognizable isolation from the collective aspirations of the institution. Although most likely unintended, these subtle facets of the international institution serve to soften the rigidity of ‘consensus-only’ decision-making. The resulting flexible-consensus provides the opportunity for greater institutional democratization through an enhanced focus on the will of the collective.

The principal coalescing element of this institution is not its compulsion mechanisms but its mutually shared commitment to the values and ideals on which the Washington Treaty was signed. This institution of like-minded allies was originally designed to strengthen pre-existing relationships while affording collective security against, what was perceived as a shared threat. Within this context, the framers of the treaty anticipated a ‘Union of the willing,’ a scenario that deemphasized the importance of the formal decision making process. NATO’s practice of decision solely by consensus theoretically risks: delayed action, lowest-common-denominator decision making, and even inaction resulting from stalemate. However, NATO’s constant consultative practices are designed to combat these potential inefficiencies. Moreover, decisions that are ultimately produced by the North Atlantic Council enjoy the legitimacy of representing the collective will of the organization and its members.