European Union

|  |

Name: European Union | |

| Acronym: EU | |

| Year of foundation: ECSC - 1951, EEC, Euratom - 1957, EU - 1992 | |

| Headquarters: Bruxelles, Strasbourg and Luxembourg | |

| EU documents: go to page | |

| Official web site: go to page | |

FOCUS ON | |

Description

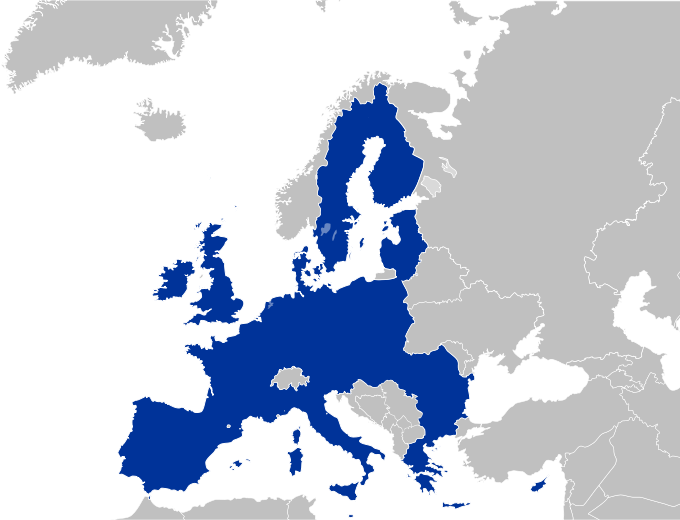

The European Union (EU) is an economic, monetary and political union of 27 Member States, committed to regional cooperation and integration.

It represents the most advanced form of economic and political integration and co-operation among regional organizations in the world.

While the European Communities were founded in 1951 and 1957, respectively with the Treaties of Paris (European Coal and Steel Community - ECSC) and Rome (European Economic Community - EEC and Euratom), the EU was established by the Treaty of Maastricht signed in 1992 but entered into force on 1 November 1993 upon the foundations of the pre-existing European Economic Community, plus the political Union and the European Monetary Union (EMU). With 500 million citizens, the EU generates an estimated 30%of the nominal gross world product. The EU budget for 2010 is €141.4 billion in commitments and €122.9 billion in payments and, even if legally limited to 1.27% and practically to 1% of the EU total GDP, represents many hundreds times the OSCE’s and the Council’s of Europe budget.

The EU is the world’s strongest commercial power and the biggest aid donor to the developing world.

The EU parliamentary democracy has evolved from the early second degree parliamentary assembly to a parliament elected by citizens through universal suffrage since 1979. In 2009 the 7th European elections were held. The strengthening of parliamentary democracy was parallel to the development of a series of European regulatory powers: a single market through a system of laws applied in all member states, ensuring the free movement of people, goods, services and capital, common policies on trade, agriculture, fisheries and regional development, a common currency (the euro) adopted by 16 member states, known as the Eurozone.

Whereas its multiple external relations make it the second global actor, the EU has developed a very limited role in foreign policy, having representation at the WTO, G8 summits, the UN and other international organizations.

It enacts legislation on justice and home affairs, including the abolition of passport controls among many member states which signed the Schengen Agreement.

As an international organization sui generis the EU operates through a hybrid system of supranational and intergovernmental institutions and procedures. In certain areas, it depends upon unanimous agreement between the member states; in others, supranational bodies, including the Parliament and Council, are able to make decisions without unanimity, based on the Commission proposals.

Important EU institutions and bodies include the European Commission, the Council of the European Union, the European Council, the European Court of Justice, and the European Central Bank.

Number and Member countries: 27

| Member country | Flag | Date of membership |

France | | Founder |

Germany | | Founder |

Italy | | Founder |

Belgium | | Founder |

Netherlands | | Founder |

Luxembourg | | Founder |

Denmark | | 1973 |

Ireland | | 1973 |

United Kingdom | | 1973 |

Greece | | 1981 |

Portugal | | 1986 |

Spain | | 1986 |

Austria | | 1995 |

Finland | | 1995 |

Sweden | | 1995 |

Cyprus | | 2004 |

Czech Republic | | 2004 |

Estonia | | 2004 |

Hungary | | 2004 |

Latvia | | 2004 |

Lithuania | | 2004 |

Malta | | 2004 |

Poland | | 2004 |

Slovakia | | 2004 |

Slovenia | | 2004 |

Bulgaria | | 2007 |

Romania | | 2007 |

Candidate countries

Croatia

the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia

Turkey (in 1987 formally applied to join the Community and began the longest application process for any country)

Potential candidates

Albania

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Kosovo (under UN Security Council Resolution 1244 - not all member states recognise it as an independent country separate from Serbia)

Montenegro

Serbia

Iceland

Former members

No EU member state has ever chosen to withdraw from the European Union, though some dependent territories or semi-autonomous areas have left the EU.

Only Greenland has explicitly voted to leave, in 1985, departing from the EU’s predecessor, the EEC, caused by divergences about fishing rights without seceding from the belonging member state (initially a vote against joining the EEC was expressed in 1973, but Denmark as a whole voted to join and Greenland was obliged to join too like a Danish region, while after obtaining home rule in 1979 it held a new referendum that confirmed the will to leave the EEC). However it remains subject to the EU treaties through the EU Association of Overseas Countries and Territories.

The only member state to hold a national referendum on withdrawal was the United Kingdom in 1975, when 67.2% of those voting voted to remain in the Community.

Before the Treaty of Lisbon entered into force on 1 December 2009 no provision concerned the voluntary withdraw from EU. But the European Constitution introduced this provision and it was then included in the Lisbon Treaty (art. 50 Treaty of the European Union – TEU).

History

From the Schuman Plan to the Treaties of Rome

The project of uniting Europeans and European States emerged after World War II in order to promote the reconciliation between the two historical enemies, France and Germany, and escape the resurgence of armed nationalisms in the continent. A new course towards integration and a future federal unity of Europe was conceived through an original political project of peace: on 9 May 1950, the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, Robert Schuman, proposed a plan, elaborated by the head of France's General Planning Commission, Jean Monnet, to place coal and steel production (on which the making of war weapons depends) under the control of an independent High Authority in the context of a limited but supranational organization open to the adhesion of other European states and considered as "a first step in the federation of Europe". The Federal Republic of Germany accepted this project. Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Italy also joined it and later, after a conference and negotiations among these countries, the Treaty of Paris, signed on 18 April 1951, laid down the foundation of the European Coal and Steel Community, effective from 23 July 1952 for a fifty-year period and expiring on 23 July 2002, even if its functions and structures were transferred to the European Community. Important European politicians like the Belgian socialist Prime Minister, Paul Henri Spaak, and the Italian christian-democrat Alcide De Gasperi, were supporters of this process and along with Jean Monnet and Robert Schuman were called the “fathers of Europe”. The Europe Declaration, a joint statement of the Foreign Ministers of the Six founder members presented on 18 April 1951, declared: “By the signature of this Treaty, the participating Parties give proof of their determination to create the first supranational institution and that thus they are laying the true foundation of an organised Europe. This Europe remains open to all European countries that have freedom of choice. We profoundly hope that other countries will join us in our common endeavour”. The following attempts to create a European political union – although a Statute of European Political Community was approved in 1953 by an ad-hoc Assembly awaiting the ratification of a Treaty establishing a European Defence Community, rejected by the French National Assembly on 30 August 1954 - failed and the integration process changed direction towards the creation of a common market in other economic and commercial areas. After the Messina Conference of Foreign Ministers of the ECSC held in 1955, the six members re-launched the integration process and, through an Intergovernmental Conference (IGC), formed two new European Communities with the objective of a further economic integration. The European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom) were set up under separate treaties signed in Rome on 25 March 1957 and entered in force on 1 January 1958, with the aim of creating a customs union (achieved in July 1968) and a single internal market, including the harmonisation of some economic policies and characterised by the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital, and, even if unsuccessfully in this sector, the promotion of nuclear research, energy and industry for peaceful purposes. Each Community was organized with its own organs but their structures were very similar, including an executive body (called Commission in both the EEC and Euratom and High Authority in the ECSC) composed by independent members acting only in the Community’s interest, an intergovernmental organ representing the national governments and responsible for policy-making (called Council in both the EEC and Euratom and Special Council of Ministers in the ECSC), while a Court of Justice and an Assembly were common to all three Communities.

Developments and reforms up to the Single European Act (SEA)

A Merger Treaty signed in Bruxelles on 8 April 1965 and effective on 1 July 1967 established a single Council and a single Commission of the European Communities (also commonly known as the European Community). Since then, the EU has grown in size through different enlargements (even if British entry was delayed in the 1960s by the French President De Gaulle’s veto), and in power through the addition of policy areas to its remit. The United Kingdom, Denmark and Ireland became full members of the European Communities on 1 January 1973 and Norway, after two popular referenda, respectively in 1972 and in 1994, rejected entry and decided not to accede. Following the transition towards democracy Greece entered the EC in 1981 and later, in 1986, Spain and Portugal. After this evolution, the EC, composed by twelve European countries and democratically reinforced by the first direct elections of the European Parliament in June 1979, progressively reshaped itself through the periodic reform of the EC Treaties: the first major revision of the Treaties of Rome was represented by the Single European Act (SEA), signed in 1986 and entered in force on 1 July 1987. It modified the institutional system providing for a more powerful European Parliament in the decision-making process and for majority voting in the Council of Ministers in under some circumstances, and fostered the implementation of the completion of the unified internal market by 1993, strengthening economic and social cohesion as well as the birth of new communitarian policies, such as the European environmental policy and the creation of the European Political Co-operation (EPC) in order to develop a foreign policy co-ordination.

From the European Union to the Treaty of Lisbon

In 1990, after the fall of communism in Eastern Europe, the former German Democratic Republic became part of the unified German Communities. Through the decision of the European Council, two different Intergovernmental Conferences (one on economic and monetary union and the other on political union) worked between 1990 and 1991 in order to reform the European Communities. The result was the Maastricht Treaty, which established the European Union, signed on 7 February 1992 and entered in force only on 1 November 1993 after a difficult period of ratification (a popular referendum held in Denmark in June 1992 was negative and even though a majority yes vote prevailed in Ireland, in France, in September 1992, the Treaty was approved by a very narrow majority, while the Federal Constitutional Court declared the Treaty compatible with the German Constitution only in October 1993). It is based on three pillars (EC, Common Foreign and Security Policy – CFSP and Justice and Home Affairs Cooperation, endowed with different decision-making procedures). In June 1993 the European Council in Copenhagen defined the rules determining the eligibility of a country to join the same EU: the so-called Copenhagen criteria, require a candidate country to have achieved stability of institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human rights, respect for and protection of minorities, the existence of a functioning market economy and to accept – and be able to implement - the obligations and intent of the EU, in summary the acquis communautaire, i.e. Treaties, legislation, judgments of the Court of Justice, policies and practices agreed upon or developed within the EU. In 1995 Austria, Finland and Sweden joined the EU, increasing its membership by 15. Another reform of European institutions began in the IGC opened on March 1996 in Turin and concluded with the Treaty of Amsterdam signed in October 1997 and effective on May 1999, which simplified and consolidated the Treaties, for example providing a High Representative for CFSP (Javier Solana, former Secretary of NATO, held this position from 1999 to 2009) and incorporated into European law the Schengen Agreement signed in 1985, concerning the progressive creation of open borders without passport controls among most member state and some non-member states (22 EU and 3 non-EU states – Iceland, Norway and Switzerland, although all EU members except Ireland and the United Kingdom have to implement Schengen, including Bulgaria, Cyprus and Romania). A further IGC, opened in Lisbon in February 2000, was needed to adjust the EU’s structure so that it would be able to cope with the impact of the wide and impressive Eastern and Mediterranean enlargement. The Nice Treaty emerged on 11 December 2000 as a new compromise and was signed on 26 February 2001, coming into force on 1 February 2003, but the EU adopted a declaration on the future of Union, calling for a deeper and wider debate, also involving the candidate countries, on the perspectives of the European integration process. At the Laeken European Council, on December 2001, a decision was made to set up a Convention to debate key issues regarding the evolution of the Union and make the EU more democratic, transparent and efficient. The European Convention (the second after the Convention drafting the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union declared on December 2000) chaired by the former French President, Valéry Giscard D’Estaing, and composed of representatives of the Heads of State or Government of the member countries (one from each country) and members of the European Parliament, the European Commission and national parliaments (two from each country) as well as a similar representation of governments and parliaments of candidate countries, met between February 2002 and July 2003 and concluded its work adopting by consensus a draft Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe to be submitted to a specially IGC. Although an agreement was reached in June 2004, a month after the accession of ten new countries in the EU (the biggest enlargement in its history) – Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Hungary – and the so-called Constitutional Treaty was signed in Rome on 29 October 2004, it was rejected by two popular referenda, in France and the Netherlands, respectively on 29 May and 1 June 2005. Subsequently, although a large majority of member countries had ratified the European Constitution, the EU underwent a period of reflection and eventually a new ICG was assigned to draft a new treaty amending but not replacing (as it would have happened if the European Constitution had entered in force) the Treaty on European Union and the Treaties establishing the European Communities.

The Treaty of Lisbon, as result of this work, was signed on 13 December 2007, but an Irish referendum in June 2008 again stopped the difficult reform process because it failed to secure a majority in favour of ratification. On 1 December 2009, the Lisbon Treaty came into force after a large number of obstacles and a second referendum held in Ireland in October 2009 witnessed a prevailing “yes” to the Treaty . This outcome came subsequent to the European Council’s decision, confirming that the European Commission would continue to include one national of each Member State and an agreement about legally binding guarantees in respect of particular areas identified by Ireland including taxation, the right to life, education and the family, and the Irish traditional policy of military neutrality, would be incorporated by way of a Protocol in the EU Treaties after the Lisbon Treaty entered into force. Meanwhile, two other member countries had joined the EU in 2007, Bulgaria and Romania, the last candidates of the “Eastern” wave. In 2002 the single European currency, the euro, as the final step of the construction of European Monetary Union (EMU) replaced national currencies in 12 member states, followed also by Slovenia, Cyprus, Malta e Slovakia (16 of 27 member States are included in the Eurozone) between 2007 and 2009. The Eurozone entered its first economic recession in 2008. Members cooperated and the European Central Bank, seated in Frankfurt (Germany), intervened to help to restore economic growth. Consequently the euro was seen as a safe haven, particularly by those outside the EU such as Iceland, which in July 2009, after a harsh economic crisis, formally applied for EU membership. However, with the risk of a default in Greece and other member countries in late 2009 and 2010 (in addition to Greece, countries such as Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and, to a certain extent, Italy, collectively referred to as PIIGS) Eurozone leaders decided to agree on provisions for bailing out member states who could not raise funds, provoking a u-turn on the EU treaties which ruled out all bailouts of euro members in order to encourage them to manage their finances better. The crisis spurred consensus for further economic integration and a range of proposals such as a European Monetary Fund or federal treasury.

The Treaty of Lisbon: values, purposes, democratic principles, policies

The Lisbon Treaty amends the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community. It is the latest update that consolidates the EU’s legal basis. In this way the EU obtains its own legal personality. This change should improve the EU’s ability to act, especially in external affairs.

The European Union (EU) is founded on the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and on the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) that “have the same legal value” and has replaced and succeeded the European Community (art. 1 TEU). Constitutive values are “the respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities” and they “are common to the Member States in a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail” (art. 2 TEU).The Treaty pledges that the European Union, in order “to promote peace, its values and the well-being of its peoples” will:

• “offer people an area of freedom, security and justice without internal frontiers in which the free movement of persons is ensured in conjunction with appropriate measures with respect to external border controls, asylum, immigration and the prevention and combating of crime”;

• “establish an internal market” and “work for the sustainable development of Europe based on balanced economic growth and price stability, a highly competitive social market economy, aiming at full employment and social progress, and a high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment”;

• “promote scientific and technological advance, combat social exclusion and discrimination and promote social justice and protection, equality between women and men, solidarity between generations and protection of the rights of the child”;

• “promote economic, social and territorial cohesion, and solidarity among Member States”;

• “remain committed to an economic and monetary union with the Euro as its currency”;

• “uphold and promote the European Union’s values and interests in the wider world and contribute to the protection of its citizens, peace, security, the sustainable development of the Earth, solidarity and mutual respect among peoples, free and fair trade, and the eradication of poverty”;

• “contribute to the protection of human rights, in particular the rights of the child, as well as to the strict observance and development of international law, including respect for the principles of the United Nations Charter” (art. 3 TEU).

“The limits of Union competences are governed by the principle of conferral. The use of Union competences is governed by the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality”. Thus “competences not conferred upon the Union in the Treaties remain with the Member States” (art. 5 TEU).

According to the principle of subsidiarity the EU’s decisions must be taken as closely to the citizens as possible. This principle is complemented by the proportionality principle whereby the EU must limit its action to that which is necessary to achieve the objectives set out in the Lisbon Treaty.

Moreover “the Union recognises the rights, freedoms and principles set out in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union of 7 December 2000, as adapted at Strasbourg, on 12 December 2007”, which have the same legal value as the Treaties (art. 6 TEU). Therefore, the Lisbon Treaty makes the Charter legally binding. “The Union shall accede to the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. Such accession shall not affect the Union’s competences as defined in the Treaties. Fundamental rights, as guaranteed by the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms and as they result from the constitutional traditions common to the Member States, shall constitute general principles of the Union's law" (art. 6 TEU).

Regarding provisions on democratic principles “in all its activities, the Union shall observe the principle of the equality of its citizens, who shall receive equal attention from its institutions, bodies, offices and agencies” and “every national of a Member State shall be a citizen of the Union” but “citizenship of the Union shall be additional to national citizenship and shall not replace it” (art. 9 TEU).

The Lisbon Treaty states the “the functioning of the Union shall be founded on representative democracy” and “citizens are directly represented at Union level in the European Parliament”, while “Member States are represented in the European Council by their Heads of State or Government and in the Council by their governments, themselves democratically accountable either to their national Parliaments, or to their citizens”. Moreover, the Treaty declares that “every citizen shall have the right to participate in the democratic life of the Union” and “decisions shall be taken as openly and as closely as possible to the citizen”. Finally “political parties at European level contribute to forming European political awareness and to expressing the will of citizens of the Union” (art. 10 TEU).

Article 11 TEU concerns public participation and civil society and declares: “the institutions shall, by appropriate means, give citizens and representative associations the opportunity to make known and publicly exchange their views in all areas of Union action” and also “maintain an open, transparent and regular dialogue with representative associations and civil society”, while “the European Commission shall carry out broad consultations with parties concerned in order to ensure that the Union's actions are coherent and transparent”.

Furthermore, for the first time, the Lisbon Treaty provides a new Citizens’ Initiative: one million people - out of the EU’s population of 500 million - from a number of Member States can petition the European Commission to bring forward new policy proposals. Finally, to improve information about how the EU reaches decisions, the Council of Ministers will now have to meet in public when it is considering and voting on draft laws. The Treaty has increased the number of areas where the European Parliament shares decision-making with the Council of Ministers, resulting in a better capacity to act in lawmaking and to decide completely upon the EU Budget.

The role of national parliaments is also more incisive as they have greater opportunities to make a direct input into EU decision-making. Indeed a new early warning system gives national parliaments the right to comment on draft laws and check that the EU does not overstep its authority by involving itself in matters best dealt with nationally or locally.

All national parliaments have eight weeks to argue the case if they feel a proposal is not appropriate for EU action and finally, if enough national parliaments object, the proposal can be amended or withdrawn.

The EU’s role in the area of common foreign and security policy is reinforced but decisions on defence issues will continue to require unanimous approval by the 27 EU Member States. Since 2003 military, civil and mixed civil-military missions, which the EU has undertaken outside its own territory (from the former Yugoslavia to Africa, from the Middle East to Indonesia) implementing the new European Defence and Security Policy (EDSP) developed after the Kosovo war in 1999, have been for the purpose of peacekeeping, conflict prevention and strengthening of international security within the framework of the United Nations Charter. The European Council held in Cologne in June 1999 agreed that "the Union must have the capacity for autonomous action, backed by credible military forces, the means to decide to use them, and the readiness to do so, in order to respond to international crises without prejudice to actions by NATO". The European Council in Nice decided to establish permanent political and military structures in this field: the Political and Security Committee (PSC), the European Union Military Committee (EUMC); the Committee for Civilian Aspects of Crisis Management (CIVCOM); the European Union Military Staff (EUMS); the Civilian Planning and Conduct Capability (CPCC). Beyond the introduction of the High Representative of the Union for Foreign and Security Policy/ Vice-President of the Commission, the Lisbon Treaty extends the EU’s role to include disarmament operations, military advice and assistance, and helping to restore stability after conflicts. It also creates the possibility of enhanced cooperation between member states that wish to work together more closely in the area of defence. Enhanced cooperation means that a group of countries can act together without all 27 necessarily participating so allowing member states to remain outside if they do not wish to join, without stopping other Member States from acting together. The Treaty provides that Member States will make available to the EU the civil and military capability necessary to implement the Common Security and Defence Policy and sets out the role of the European Defence Agency. A voluntary solidarity clause is introduced when a Member State is the victim of a terrorist attack or a natural or man-made disaster. The role of the Western European Union (WEU) - a military alliance with a mutual defence clause, founded on the Bruxelles Treaty (1948) and set up in 1955 by the EC's Six Member States and the United Kingdom as intergovernmental body after the failure of the European Defence Community- was transferred to the EU and the WEU disbanded in March 2010 (its activities will cease within 2011).

The Lisbon Treaty introduces a renewal of the European environmental policy giving priority to the EU’s objective of promoting sustainable development in Europe, based on a high level of environmental protection and enhancement and of facing the climate change. EU pledges to promote, at an international level, measures to tackle regional and global environmental problems, in particular climate change in order to combat global warming. Moreover, the Treaty affirms the EU’s commitment to a united European policy on sustainable energy and includes new provisions ensuring that the energy market functions well, in particular with regards to energy supply, and that energy efficiency and savings are achieved, as well as the development of new and renewable energy sources.

The Treaty also provides a new basis for cooperation between Member States in sport, humanitarian aid, civil protection, tourism and space research.

EU structure and decision-making procedures

Competences

The EU has exclusive control over customs union, competition rules for the functioning of the internal market, the conservation of marine biological resources under the common fisheries policy, the common monetary policy of the Euro area and the common commercial policy.

The EU and the Member States share competences in the following areas: internal market (also the non-EU member states of Iceland, Norway, Liechtenstein and Switzerland participate in the single market but not in the customs union); social policy (limited to the aspects defined in the Treaty); economic, social and territorial cohesion; agriculture and fisheries; environment; consumer protection; transport; trans-European networks; energy and in the area of freedom, security and justice.

The Member States have primary responsibility in fields such as the protection and improvement of human health, industry, culture, tourism, education, youth, sport and vocational training, civil protection (disaster prevention), administrative cooperation, health, education and industry.

Decision-making: the 'institutional triangle'

The EU's decision-making process in general and the co-decision procedure in particular involve three main institutions:

§ the European Parliament, which represents the EU’s citizens and is directly elected by them;

§ the Council of the European Union, which represents the individual member states;

§ the European Commission, which seeks to uphold the interests of the Union as a whole.

This ‘institutional triangle’ produces the policies and laws that apply throughout the EU. In principle, it is the Commission that proposes new laws, but it is the Parliament and Council that adopt them. The Commission and the member states then implement them, and the Commission ensures that the laws are properly taken on board.

Two other institutions have a vital part to play: the Court of Justice upholds the rule of European law, and the Court of Auditors checks the financing of the Union’s activities.

The European Parliament

The European Parliament is the directly-elected EU institution that represents the citizens of the Member States. The Treaty increases the number of areas where the European Parliament will share the job of lawmaking with the Council of Ministers and strengthens its budgetary powers. Co-decision, i. e. the sharing of power between the EP and the Council of Ministers, is nowadays the 'ordinary legislative procedure' and it extends to new policy areas such as freedom, security and justice, reinforcing the legislative powers of the European Parliament and his capacity to approve, in every single section, the EU’s budget. Thus the decision making of the European Union is based on the double legitimacy of the people (as represented by their MEPs in the European Parliament) and the member states (as represented by the Ministers in the Council). For further details about the EP see Focus European Parliament (at the top of this page)

The European Council

The European Council is made up of the Heads of State or Government of the member states and of the President of the Commission and usually meets four times a year in Bruxelles.

It defines EU’s policy agenda, its priorities and general political guidelines and is involved in the negotiation of the treaties. Under the Lisbon Treaty, the European Council becomes a full EU institution and its role is clearly defined.

The President of the European Council is a new post created by the Treaty of Lisbon in order to give stability and consistence to the EU’s action; the President is elected by the members of the European Council and can serve for a maximum of five years and co-exists with the six-month EU Presidency guaranteed in turn by each member state. The first permanent President of the European Council is the former Belgian Prime Minister, Herman Van Rompuy, who assumed office on 1 December 2009.

The Council of the EU (Council of Ministers)

The Council of the European Union (also called with the latin equivalent "Consilium" or commonly the Council of Ministers) is made up of 27 government ministers representing each of the Member States.

It is a key decision-making body that coordinates the EU’s economic policies and plays a central role in foreign and security policy. It shares lawmaking and budgetary powers with the European Parliament. Qualified majority voting (from 2014 decisions of the Council of Ministers will need the support of 55% of the Member States, representing at least 65% of the European population) instead of unanimous decisions, it is extended in order to make action faster and more efficient. At least 4 countries will be needed to form a blocking minority. Every Member State must agree the possible extension of the qualified majority’s application and the national parliaments have a right of veto. important policy areas such as taxation and defence will continue to require a unanimous vote.

A Committee of Permanent Representatives of the Governments of the Member States is responsible for preparing the work of the Council.

A new development under the Treaty is that the Council of Foreign Ministers is chaired by the High Representative of the Union for Foreign and Security Policy/ Vice-President of the Commission, appointed by the European Council and that combines two different existing posts before the Treaty of Lisbon: the High Representative for Common Foreign and Security Policy and the External Relations Commissioner. The new position of High Representative (Catherine Ashton was the first one, nominated in 2009) will be assisted by a dedicated European External Action Service (EEAS).

In other areas such as agriculture, finance and energy, the Council continues to be chaired by the Minister of the country holding the rotating six-month EU Presidency.

The European Commission

The European Commission is the executive and administrative organ, also regarded as the motor of the EU. It represents, independently, the interests of the EU as a whole and it is the only EU institution with the general power to initiate proposals for legislation.

It also has the power of execution and the tasks of implementing the Treaties and the EU’s budget, enforcing EU policies, managing EU programmes, representing the EU in international negotiations and making sure that the Treaties are applied entirely and properly.

The Commission is accountable to the European Parliament and consists of 27 members, one from each country, chosen on the grounds of their general competences and appointed for a renewable five-year term.

The President is nominated by the European Council and is consulted for the nomination of the other Commissioners. President and Commissioners are subject to a vote of approval by the European Parliament.

The Court of Justice of the EU

The Court of Justice represents the judicial branch of the EU, consisting of three courts seated in Luxembourg: the Court of Justice, the General Court (previously known as "the Court of First Instance") and the EU Civil Service Tribunal. The Court of Justice is composed of 27 judges, one judge from each member state, assisted by 8 advocates-general, all appointed for renewable six-year terms by common accord between the member states among persons whose independence is unquestionable and who fulfil the condition required for the exercise of the highest juridical functions in their respective countries or are legal experts of universally recognized ability. This court deals primarily with cases taken by member states, the institutions and cases referred to it by the courts of member states. It can judge member states over EU law. The General Court, born in 1989, have jurisdiction to hear and determine certain categories of cases taken by individuals and companies directly before EU’s courts. His decision can be appealed to the Court of Justice, but only on a point of law.

The EU Civil Service Tribunal adjudicates in disputes between EU and its civil service.

The European Central Bank

The Treaty of Lisbon includes the European Central Bank (ECB) as an independent institution of the European Union. It was set up in 1998 by the Treaty of Amsterdam and is headquartered in Frankfurt (Germany). It is responsible for the implementation of the European monetary policy and its primary objective is to safeguard price stability within the Eurozone by controlling the money supply and monitoring price trends. It consists of three decision-making bodies: the Executive Board, the Governing Council and the General Council.The Executive Board, comprising the President of the Bank, a Vice President and four other members (all appointed by common accord of the Eurozone member states for a non-renewable term of eight years), is responsible for the implementation of monetary policy defined by the Governing Council (composed by the Executive Board and the governors of the central banks of the Eurozone and responsible for the day-to-day running of the bank and for defining the monetary policy, and, in particular, for fixing the interest rate at which the commercial banks can obtain money from the Central Bank. The General Council (consisting of the ECB’s President and Vice-President and the governors of the national central banks of all 27 EU member states) contributes to the ECB’s advisory and coordination work in order to prepare the future enlargements of the Eurozone.

The Court of Auditors

The Court of Auditors carries out the Union's audit. The Court’s main role is to check that the EU budget is correctly implemented. It consists of one national of each Member State. Its Members shall be completely independent in the performance of their duties, in the Union's general interest, and are chosen among persons who belong or have belonged in their respective States to external audit bodies or who are especially qualified for this office. The Members of the Court of Auditors shall be appointed for a six-year term. The Council, after consulting the European Parliament, shall adopt the list of Members drawn up in accordance with the proposals made by each Member State. The term of office of the Members of the Court of Auditors shall be renewable. The Court of Auditors shall examine the accounts of all revenue and expenditure of the Union. It shall also examine the accounts of all revenue and expenditure of all bodies, offices or agencies set up by the Union in so far as the relevant constituent instrument does not preclude such examination. One of its key functions is to help the European Parliament and the Council by presenting them every year with an audit report on the previous financial year. Parliament examines the Court’s report in detail before deciding whether or not to approve the Commission’s handling of the budget. If satisfied, the Court of Auditors also sends the Council and Parliament a statement of assurance as to the reliability of the accounts and the legality and regularity of the underlying transactions which shall be published in the Official Journal of the European Union. Finally, the Court of Auditors gives its opinion on proposals for EU financial legislation and for EU action to fight fraud.

Other bodies - Consultative bodies: The Committee of the Regions, The European Economic and Social Committee - Financial bodies: The European Investment Bank (EIB), The European Investment Fund - Intersectorial bodies: The Publications Office of the European Union, European Personnel Selection Office, European Administrative School - Community agencies - Other specialised bodies: European Ombudsman, European Data Protection Supervisor