North American Free Trade Agreement

|  |

Name: North American Free Trade Agreement | |

| Acronym: NAFTA | |

| Year of foundation: 1994 | |

| Headquarters: Mexico City (Mexico), Ottawa (Canada), Washington D.C. (USA) | |

| NAFTA documents: go to page | |

| Official web site: go to page | |

Description

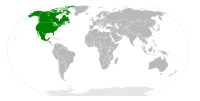

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is an agreement signed by Canada, Mexico, and the United States and entered into force on 1 January 1994 in order to establish a trilateral trade bloc in North America.

Member States

NAFTA has three member States, namely Canada, Mexico and United States.

History

Events Leading up to NAFTA

Prior to NAFTA, Canada and the United States were developed economies with strong traditions of liberal political and economic policies, while Mexico had neither. After World War II, Mexico engaged in protectionism and import-substitution, as opposed to export-led growth. Mexico’s policies were intended to create independence from American hegemony and encourage domestic industrialization through state and corporatist policies. These policies backfired and by the 1980s Mexico had triple-digit inflation, backward industries, and extensive international debt. In this environment, Mexico began to liberalize in 1985 and tear down its protectionist policies. However, Mexican wages were still just one seventh of those in the United States just prior to NAFTA. This created significant opposition to cooperation with Mexico in the United Sates, where American labour and union groups feared large job losses to Mexico. Ross Perot famously paraphrased this fear among Americans with his “giant sucking sound” metaphor for jobs going south of the US border to Mexico. For Mexico’s part, opening its economy as required by NAFTA threatened political and economic leaders who had controlled and distributed state revenues without external interference. Much smaller differences existed between the US and Canadian economic and political system, which were both liberal democracies with far more open economies.

The impediments to regional cooperation in North America were indeed real but this did not stop political leaders from realizing the benefits of integration and reaching across their borders. The first move was made by Ronald Reagan in the US, who proposed a “North American Agreement” to facilitate regional cooperation. As president, Reagan made good on his campaign pledge and declared a North American common market was a future goal. During the early 1980s and while Mexico remained aloof, Canada and the US grew closer and signed a series of agreements that culminated in the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement in 1988. At this crucial juncture, Mexico signalled it was ready to join the negotiations and NAFTA talks were started.

The NAFTA agreement was a free trade agreement (FTA), but it served as a framework for further regional cooperation. From the beginning, to get NAFTA passed Bill Clinton insisted on environmental and labour protections to assuage the fears Americans had regarding Mexico, a large and poor country. Unlike earlier absorptions of poorer countries like Spain and Portugal by the European Community (EC), where the income difference was ½ and the population only 13 percent of the EC total, Mexico’s income was 1/7 of the US and population 24 percent of North America. Given the size and nature of this disparity, significant job losses could be expected in the US and Canada, especially among low skilled jobs. The challenge for the US and Canada was then to improve education and transform their workforces into higher educated and more skilled ones. For Mexico, the challenges were more political and economic, making sure the government remained committed to transparency and an open economy. As will be seen in the following section, NAFTA was designed to allay these fears, and limit the anxieties of stakeholders who would risk much by engaging in regional cooperation in unchartered territory.

Effects of NAFTA and Recent Events

In spite of its limited institutionalization, the effects of NAFTA are profound and perhaps best understood by reference to the agreement itself. Article 102 of NAFTA describes the purpose of the treaty, which is the creation of a framework for further regional cooperation. More than a typical trade agreement, NAFTA covers competition law (Chapter 15), intellectual property (Chapter 17), investment (Chapter 11), and government procurement (Chapter 10). By subjecting these traditional vestiges of national sovereignty to review by multinational NAFTA panels, NAFTA is bestowed with a supranational character. While this judicial mechanism has some exceptions for national security and product safety, it does create a largely effective enforcement mechanism. Thus, the panel dispute settlement mechanism designated in Chapter 20 is not a court per se, but it serves essentially the same function by reviewing and providing an alternative to national decisions.

NAFTA has altered the political landscape in North America by putting free trade and economic cooperation on a firm footing. By making economic transactions transparent and secure in the region, the demand for political institutions has developed to govern these transactions. This functionalist finding has been called the “Europeanization” of North America as cross-border technical harmonization and domestic effects have created a demand for further institutionalization. The political reaction to events in the region since the signing of NAFTA supports this finding. Leaders have collaborated on everything from terrorism after 2001 to cooperation on regional infrastructure such as the proposed NAFTA superhighway running from Canada to Mexico. Compared to the post-World War II period prior to the signing of NAFTA, regional cooperation, especially with Mexico, has grown exponentially.

A quick summary of recent events demonstrates regional cooperation under the NAFTA framework. When the Mexican debt crisis broke out in 1995, US president Clinton announced a multi-billion dollar aid plan and Mexico repaid the loan early. These cooperative efforts were perceived as necessary to preserve the NAFTA system and as such were instructive for future regional financial institutionalization. In addition to financial cooperation, greater cooperation on regional energy, terrorism, health, emergency management, and a competition commission have all been developed since. As the size of cross-border transactions increases, actors lobby their governments for more regional cooperation to lock in their positions. Events such as the 9/11 terrorist attacks that shut down regional borders created pressure for a common regional border security system. Similar forces are at work in many industries previously sheltered from international competition. The cumulative effect of these forces creates a demand for institutionalization.

Another important effect of NAFTA has been the model it has offered the rest of Latin America. At present, Central America, Chile, and the Caribbean have signed free trade agreements with NAFTA. This offers poorer countries in Latin America an important path to development and support for national democratization. By gaining access to larger markets and opening economic and political institutions, development is also enhanced. However, without basic infrastructural development many countries in Latin America will still find it difficult to compete. This indicates successful regional integration for poorer countries requires development funds similar to those the EU provided southern and eastern European countries. If the goal of Mexican president Vincente Fox of a common market is to be realized, fiscal transfers will have to precede the free movement of goods, services, and people in order to make it politically palatable. According to Fox: "Our forecast and our idea is to sell a long-term project where we can move upwards from a trade agreement to a community of nations agreement or a North American common market. To move in that direction implies more than just trading, more than just facilitating the transit of merchandises, products, services, and capital. It has to imply the free flow of citizens, and it has to imply long-term monetary policies, maybe a common currency 20, 30, 40 years from now. Should this path for NAFTA materialize, it is sure to influence the rest of the Western Hemisphere and further integration may depend on it.

While there are many benefits of NAFTA, there are problems that pose challenges to the legitimacy of the regional experiment in North America. Economically, NAFTA has been blamed for “deindustrialization” in the United States as manufacturing jobs migrated to Mexico. In Mexico, NAFTA is blamed for the impoverishment of rural areas as cheap subsidized American corn imports displaced local producers. Further north in Canada, the main complaint is cultural domination by the United States and the loss of independent Canadian media firms. As with the freedom that democracy grants, costs and benefits are associated with regional cooperation. Loss of independence is not necessarily a negative when it is replaced by a system of interdependence. A regional institutional demand is now being created by problems caused by NAFTA that demand resolution from affected persons. If regional democratic institutions do not arise to address these problems, there is a danger of dependence and domination which leads to undemocratic and unstable outcomes.

NAFTA Structure and Decision-making Procedures

NAFTA's governance structure is minimal and cantered on two institutions, the Free Trade Commission (TFC) and the Secretariat.

The Free Trade Commission (FTC)

The Free Trade Commission (FTC) is the principal body of NAFTA, and oversees NAFTA’s performance and evolution. It is also responsible for dispute settlement, and is composed of the US Trade Representative, the Canadian Minister for International Trade, and the Mexican Secretary of Commerce and Industrial Development. The day-to-day work of the FTC is carried out by expert working groups and committees. This authority was laid out in Article 2001 (2) of the NAFTA, which gave express power to the FTC to oversee, resolve, and supervise the work of “all committees and working groups established under…[the NAFTA]…Agreement”. The FTC also has implied power in Section 2001 (3) to “establish…delegate, seek the advice of non-governmental…groups and take…other [unspecified] action”. These powers are enforced annually at trilateral cabinet-level meetings as prescribed by Article 2001, or in actions that review national court decision affecting North American Trade.

The powers of the FTC can be characterized as technical, specific, and obligatory. The FTC operates by consensus and has no effective method of amending NAFTA rules. Lacking the ability to delegate power or vote by majority rule as a legislature might, the FTC suffers from a democratic deficit and this could damage its long term legitimacy (Maryse 2006). While this minimal institutionalization will need to be reformed in the long run if NAFTA is to be viable, the technical nature of NAFTA is in keeping with the functionalist approach. Also in view of this, it is no surprise that NAFTA focuses on precision and obligation and eschews delegation of power (Abbott 2000). At the time NAFTA was negotiated, political constraints among North American leaders prohibited greater regional democratization.

The Secretariat

The Secretariat serves as an administrator for the FTC and is organized on a national basis, with each member responsible for supporting its own staff. Operationally, the secretariat assists the FTC, along with the dispute panels, committees, and working groups. The Secretariat is located in separate national offices in Mexico City, Ottawa and Washington (Lopes Lima 1997). This decentralized structure does not mean the secretariat has any real power of its own through delegation from the FTC. Instead, it takes care of the day-to-day affairs that are prescribed by Article 2002. If the FTC directs it under Article 2002 (a)(c) to administer a trade dispute panel, it must adhere to the guidelines of Article 2012. This high level of legalization constrains the secretariat from acting independently and insures real decisions are made by the FTC or panels rather than at the discretion of secretariat staff. This low level of delegation limits the responsiveness of the secretariat to exogenous groups such as labour or environmental groups and guarantees that free trade and investor interests will be guarded vociferously. As interests inevitably collide with greater interactions, this democratic deficit may need to be remedied by a court or legislature with regional authority.

The national secretariats are also complemented by a NAFTA Coordinating Secretariat (NAFTACS) based in Mexico. This trilateral secretariat was created on January 14, 1995. The main purpose of the central secretariat is to help administer labour and environmental issues that fall under NAFTA. In reality, due to limited enforceability and lax regulation, this body has not been very active, and is unequal in power to the investment and free trade lobbies. Going forward, US domestic opposition to NAFTA is great among the environmental and labour communities and will grow as interests clash. This means that the international secretariat needs greater authority to overcome the narrow interests of business elites in each country, and thus endow NAFTA with democratic legitimacy.