Southern Africa Development Community

|

|

| Name: Southern African Development Community | |

| Acronym: SADC | |

| Year of foundation: 1980 (SADCC); 1992 (SADC) | |

Headquarters: Gaborone, Botswana | |

SADC documents: go to page | |

SADC official web site: go to page | |

FOCUS ON | |

| SADC Parliamentary Forum |

Description

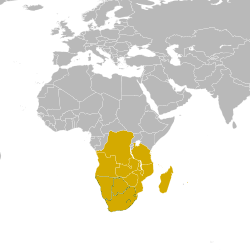

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) is an inter-governmental organization headquartered in Gaborone, Botswana. Its goal is to further socio-economic cooperation and integration as well as political and security cooperation among 15 southern African states. It complements the role of the African Union.

Member states

SADC has 15 member states, namely:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Suspended

![]()

History

The SADC forerunners: The FLS and SADCC

SADC is one of the oldest regional inter-state organisations in Africa with its almost 30 years of operation. Its origins lie in the 1960s and 1970s, when the leaders of majority-ruled countries and national liberation movements coordinated their political, diplomatic and military struggles to bring an end to colonial and white-minority rule in southern Africa, particularly to the repressive South African apartheid regime. In this context, the Front Line States (FLS) was formed, a regional loose coalition of newly independent states with the aim of uniting against South African expansionism and supporting further decolonisation.

The Southern African Development Co-ordination Conference (SADCC) was born as further consolidation of the FLS. The SADCC was formed around four principle objectives: 1) To reduce member states dependence, particularly but not only, on apartheid South Africa; 2) To implement projects and programmes with national and regional impact; 3) To mobilise member states’ resources in the quest for collective self-reliance; 4) To secure international understanding and support.

The leaders of the region’s majority-ruled countries; Angola, Botswana, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia, Swaziland, Lesotho, Malawi and the newly liberated Zimbabwe signed the SADCC Memorandum of Understanding in Zambia 1981 providing for the organisation’s institutions and rights and obligations. Gaborone in Botswana was chosen as the site for the headquarter. Also, the SADCC Programme of Action was adopted, spelling out the functional co-operation activities in various sectors including transport and communication, energy, mining, trade and food and agriculture.

SADCC adopted a decentralised approach to regional co-operation, which meant that became a rather loose form of co-operation built on concrete projects and programmes. Responsibility for project planning and implementation, as well as funding, was given to individual states; thereby the need for an expensive bureaucracy was downplayed. Besides individual project running, each member was given one of the above mentioned sectors to co-ordinate, and thus an equal stake in the organisation regardless of the degree of economic and political power. Therefore, SADCC in itself did not legally own a project or its assets and in fact did not even have a legal status.

From the start, it became evident that SADCC was heavily donor dependent. The South Africa’s long-running destabilisation was not in line with Western interests, which instead sought to stabilise the region. SADCC became one important instrument for the donors in that endeavour, albeit for different reasons depending on the donor country. The Nordic and likeminded countries saw SADCC as an important tool in the antiapartheid struggle whereas for Britain and Germany development assistance served as an alibi for maintaining economic relations with South Africa despite wide-spread sanctions.

The creation of the SADC

In the late 1980s regional policy-makers wanted to take SADCC one step further creating a more effective organisation as well as endowing it with legal status. They also realised that South Africa and Namibia strongly approached a democratic rule and had to be drawn into formal regional co-operation. Hence, the leaders of the region decided to formalise SADCC and transform it from mere project co-ordination to a much more ambitious regional agenda: SADC (le Pere and Tjönneland 2005). Furthermore, in line with a world-wide neoliberal trend in the 80-ies, the SADCC- countries started to pay more attention to promoting the private sector, foreign investment and trade. Within SADCC, members encouraged each other to reform their economies and liberalise trade in order to attract foreign investors. The creation of SADC should be seen in this light.

The Southern African Development Community was launched on the 17 August 1992 when the Windhoek Declaration and the SADC Treaty were signed by the SADCC-leaders, plus Namibia who gained its independence in 1990. Later, the original SADC-members were accompanied by South Africa (1994), Mauritius (1995), Seychelles (1998), the DRC (1998) and Madagascar (2005). With the establishment of SADC, the focus shifted from the co-ordination of, mostly, national affairs to regional integration and co-operation (Oosthuizen 2006, 70). SADC went from being a conference to a legally established and internationally acknowledged international organisation with, at least on paper, a distinct identity.

SADC agenda is very ambitious. According to the SADC Treaty, the (quite diverse) objectives of SADC are to:

“a) achieve development and economic growth, alleviate poverty, enhance the standard and quality of life of the people of Southern Africa and support the socially disadvantaged through regional integration;

b) evolve common political values, systems and institutions;

c) promote and defend peace and security;

d) promote self-sustaining development on the basis of collective self-reliance, and the interdependence of Member States;

e) achieve complementarity between national and regional strategies and programmes;

f) promote and maximize productive employment and utilization of resources of the Region;

g) achieve sustainable utilization of natural resources and effective protection of the environment;

h) strengthen and consolidate the long standing historical, social and cultural affinities and links among the people of the Region” (1992).

Also referred to as the SADC Common agenda, these objectives gave the new SADC a stronger focus on regional economic integration as well as opening up for new political areas like peace and security. In fact, In the SADC Summit of 1992 stressed the importance of creating regional peace and security arrangements and the subsequent Treaty provided for a SADC Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Co-operation (OPDSC), which was not set up until 1996. Besides the objectives relating to creating stability in the region, co-operating in conflict-prevention, management and resolution, developing a defence pact and co-operating around policing, the Organ should facilitate and support the development of democratic institutions and practices within the member states and encourage the implementation of human rights throughout the region.

Approaching the millennium, SADC started to realize the vast gender inequalities in the region and put gender firmly on the SADC-agenda.

SADC recent history

From 2001 and onwards SADC embarked on a major restructuring process. During the 90s it was felt that the decentralized approach made it very difficult for SADC to achieve its socio-economic and political objectives. The fact that each member state was responsible for a particular sector and charged with implementing projects in that sector made SADC highly vulnerable. The Secretariat proved to be rather powerless, only involved in policy coordination and project implementation.

Also, the idea that member states were best suited for regionally coordinating specific sectors proved wrong considering the fact that the majority of SADCs projects were national projects dressed up as regional.

The SADC-leaders therefore decided to fundamentally change the institutional set-up of SADC and speed up project implementation. An amended SADC Treaty was signed on the 14 August 2001, resulting in some new institutions and broadened scope for some of the old ones. One important dimension of the new SADC Agenda was that civil society, worker’s and employer’s organizations and the private sector were considered, much more explicit than before, key stakeholders to be more involved in the regional project.

Perhaps the most profound novelty of the new SADC was that the 21 co-operation sectors were clustered into four Directorates centralized to the Secretariat. Even if the responsibility for implementing projects within these four areas still lied with the member state, the Secretariat via the Directorates would provide much more of overall co-ordination and monitor implementation of protocols and analysis of policies.

Most importantly, the Treaty objectives from 1992 were developed, putting more emphasis on democracy and development. The Organ on Politics, Security and Defence Co-operation was seen as important in this endeavor, formally becoming a SADC-body residing at the Secretariat.

Furthermore, realizing that HIV/AIDS had become real threats to widespread development, SADC took on the challenge to combat the pandemic, which were to be addressed in all SADC activities.

At the time of the great restructuring process SADC also embarked on a major prioritization scheme regarding its programmes and activities. These were hectic times for SADC. It put considerable effort into developing strategic programmes to ensure a proper regional focus for its activities. The main programme in the social and economic field became the new Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan (RISDP), often referred to as SADC’s main socioeconomic development plan.

On the political side SADC developed a Strategic Indicative Plan for politics, defence and security co-operation (SIPO) for the Organ, equivalent to the RISDP, approved by the 2003 Summit in Tanzania. The SIPO provides a five-year strategic and activity guidelines for implementing the OPDS protocol. The core objective of SIPO is to create a peaceful and stable political and security environment.

The hectic days for SADC were not over. A few years ago, SADC embarked on another, yet to be completed, institutional reform process, strengthening the SADC institutional structures further. The reform focuses on strengthening SADC governance and decision making as well as management structures. In particular, the capacities and competencies of the SADC Secretariat, subsidiary organisations and SADC national institutional structures are in the process of improvement. Concretely, some major achievements have up to date been made in this regard. The decision-making structure of SADC has been more focused and its integration agenda is more prioritized. Key regional programmes are now centrally coordinated and managed by one body, the secretariat.

The latest SADC-protocol of importance here is the SADC Protocol on Gender and Development, adopted at the South Africa Summit in 2008.

In 2008, the SADC agreed to establish a free trade zone with the East African Community (EAC) and the Common Market of Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) including all members of each of the organizations.

Since 2000 began the formation of the SADC Free trade area with the participation of the SACU countries (South Africa, Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, and Swaziland). Next to join were Mauritius, Zimbabwe, and Madagascar. In 2008 joined Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Zambia bringing the total number of SADC FTA members to 12. Angola, DR Congo and Seychelles are not yet participating.

SADC structure and decision-making procedures

The Summit of Heads of State or Government

The Summit is SADC's supreme policy-making institution. It consists of the Heads of State or Government of all member states, meeting at least once a year. The Summit is responsible for the overall policy direction and control of the Organisation and its various functions, which includes, for example, reviewing the Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan (RISDP, i.e. the SADC's main socioeconomic development plan) and adopting and amending SADC Treaties, as well as appointing the Secretariat's Executive General and the judges of the Tribunal. The Summit elects a Chairperson and a Deputy Chairperson from its members for one year on the basis of rotation. The latter ascends to the Chair the coming year. Together with the previous chair they make up the Summit Troika, which functions as a steering committee and makes decisions, facilitates their implementation and provides policy directions between meetings. The current Chairperson (2009-2010), elected at the SADC Summit in Kinshasa, DRC 2009, is the Congolese President Joseph Kabila with President Hifikepunye Pohamba of Namibia as Deputy Chairperson. Together with outgoing Chairperson Jacob Zuma of South Africa they form the Summit Troika.

The Council of Ministers (COM)

The COM consists of one minister from each member state, normally the one responsible for foreign affairs, meeting at least four times a year. The Troika system applies to COM as well. COM report to and is responsible to the Summit, advising the latter on policy issues and further development of the organisation, for example recommending the Summit the approval of protocols and amendments of Treaties. It oversees the functioning of SADC and implementation of the policies and execution of programmes, including the RISDP and the Strategic Indicative Plan for Politics, Defence and Security co-operation (SIPO). The Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson are appointed by the member states holding the Chairpersonship and Deputy Chairpersonship respectively and rotate on an annual basis.

The Ministerial Clusters

The six clusters on trade, industry, finance and investment; infrastructure and services; food, agriculture, natural resources and environment, social human development and special programmes, organ of politics, defence and security co-operation and cross-cutting issues like science and technology and gender are constituted by the related ministers. They provide policy guidance to the directories at the Secretariat.

The Standing Committee of Officials

Consisting of one permanent secretary for each member state, drawn from the ministry serving as the SADC National Contact Point (see below), this committee acts as a technical advisory committee to the COM, for example processes documentation from the latter.

The Secretariat

The Secretariat is SADCs principal administrative and executive institution, situated at Gaborone, Botswana. Among its chief tasks are strategic planning and policy analysis, monitoring, coordinating and supporting the implementation of SADC programmes, implementation of decisions of supreme decision making bodies and respective troikas and representation and promotion of SADC. The Secretariat is headed by the Executive Secretary, appointed by the Summit for a once renewable four-year term. The current Executive Secretary is Dr Tomaz Augusto Salomao from Mozambique. Under him are two Deputy Executive Secretaries responsible for regional integration, i.e. the various directorates, and finance and administration. The directorates are the TIFI (trade, industry and investment), FANR (food, agriculture and natural resources) , IS (infrastructure and services), SHDSP (social and human development and special programmes) and the Directorate of the Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Co-operation.

The SADC National Committees

The rationale for the SNC-system is for SADC to make sure that each member state effectively participate in SADC-led regional integration. In theory, each member should establish SNC involving key stakeholders including government, private sector and civil society. Its composition must correspond to the clusters of sectors manifested by the directorates. The SNCs have the responsibility to provide input at national level in the SADC policy making and formulation of programmes, nationally coordinate and oversee project implementation and initiate new projects according to the RISDP. It meets at least four times a year. Linked to the SNCs are national steering committees, comprised of the chairpersons of the SNC and various sub-committees responsible for speedy implementation of programmes, and national contact points, i.e. the ministries responsible for communication with SADC.

The Tribunal

Based in Windhoek, Namibia, the Tribunal is SADC’s supreme judicial body, made up of ten judges, appointed by the Summit and chosen among qualified citizens of the SADC member states. Five of them are regular members; the other five constitute a pool of expertise, which can be drawn on whenever a regular member is temporarily absent or unable to carry out his duties. The current President of the Tribunal is Luis Antonio Mondlane from Mozambique. The Tribunal has the task to make sure that the Treaty and corresponding protocols are adhered to and deal with disputes related to their interpretation. The decision taken by the Tribunal are binding and final, and are enforced by the Summit. It may also give non-binding opinions on matters referred by the Summit or the Council of Ministers.

Partly due to resource constraints, the Tribunal became operational as late as 2005, when the first judges were appointed, 13 years after its establishment. So far, only a few cases have been tried. Therefore, the Tribunal as SADCs jurisdictional dispute-settlement body can still be considered to be in its infancy and yet the fully-fledged dispute settlement organ it is supposed to be.

The Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Co-operation

The Organ is the SADC institution responsible for promoting peace and security in SADC. Some of its objectives are to develop common foreign policy, promote political co-operation in the region and prevent, contain and resolve conflict within and between states. At the executive level, its work is coordinated by the Directorate of the Organ at the SADC Secretariat. The Organ is responsible and reports to the Summit. The leader of the Organ is always a head of state or government and the current Chairperson of the Organ is President Armando Guebuza of Mozambique and President Banda of Zambia is Deputy Chairperson. The Troika system applies to the Organ as well and together with the outgoing Chairperson Robert Mugabe, the above form the current Troika.

Decision-making within SADC

The highest policy-making institutions within SADC, i.e. the Summit and COM, in general use the consensus rule for taking decisions. Each country has one vote which means that the members have equal power in the decision-making process. Thereby, in principle, each state has the right to veto any decision, giving individual members supreme power over all decision-making. The sovereign equality principle is highly entrenched in SADC political culture. However, there are some exceptions to the consensus rule. For example, when amending the SADC Treaty weighted voting is practised. Three quarters of all members have to approve the amendment. Also, decisions regarding admittance of new members are based on unanimity.